Navigation

Learn about how to read, write and even speak Spiròt by clicking on one of the section buttons below.

Section 1: The writing system

Learn to read and write in Spiròt!

In this section you'll learn the basic written characters of the Spiròt language, how to read and write them, and how to combine them to form words. Click on one of the buttons below to get started.

In this section you'll learn the basic written characters of the Spiròt language, how to read and write them, and how to combine them to form words. Click on one of the buttons below to get started.

ARTICLE I: THE CHARACTERS

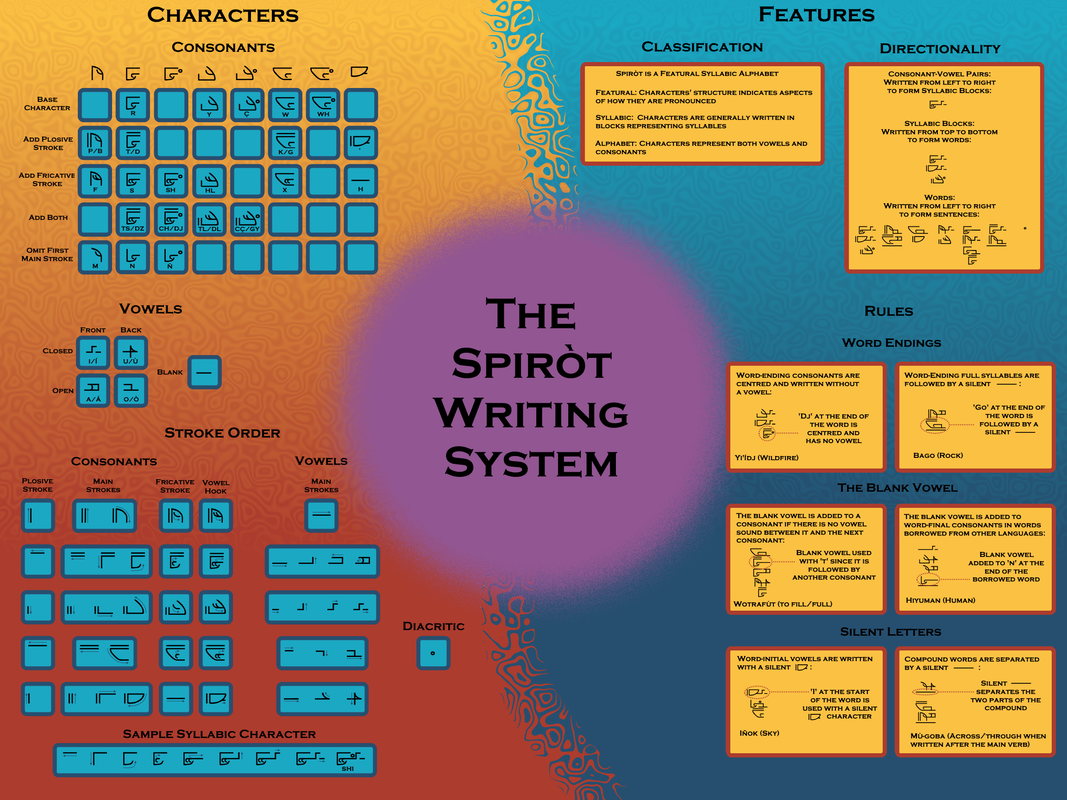

The Spiròt writing system may be considered Featural, meaning that the structure of its letters, or characters, gives an indication of their pronunciation. Furthermore, the writing system may be classified as a Syllabic Alphabet, meaning that the characters are divided into Consonants and Vowels, like an alphabet, but some of the characters, namely the vowels, cannot exist on their own. Instead, vowels are grouped with consonants to form Syllabic Characters.

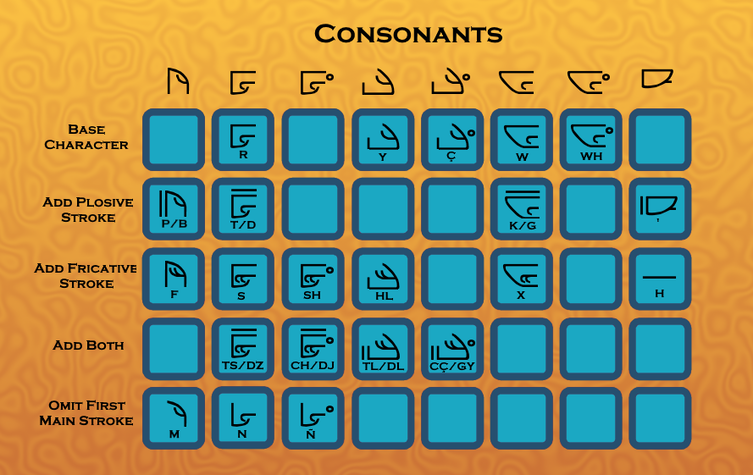

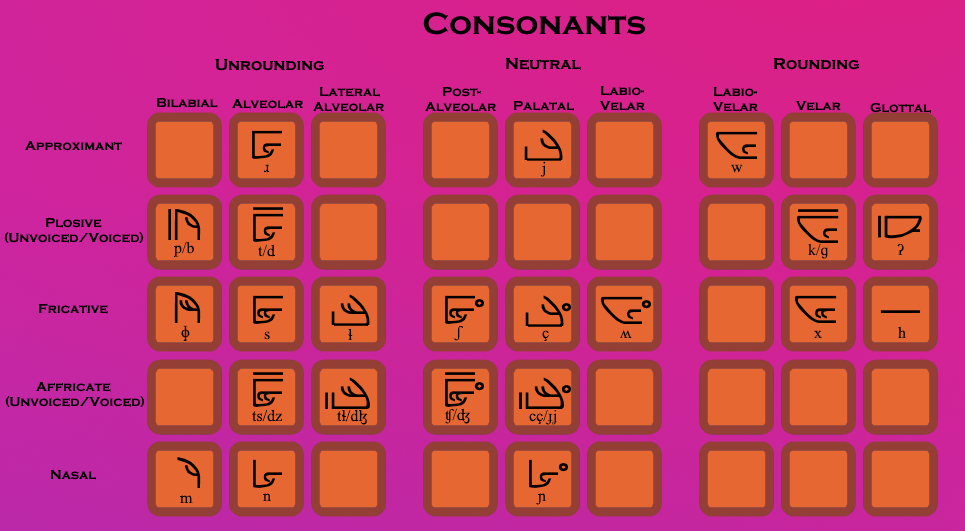

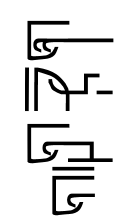

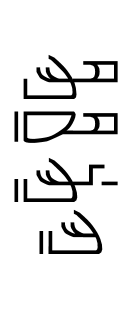

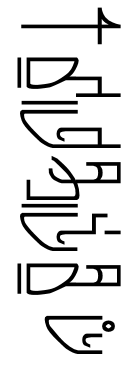

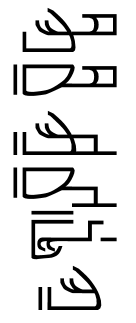

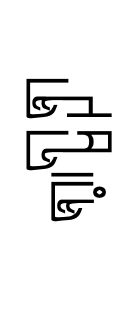

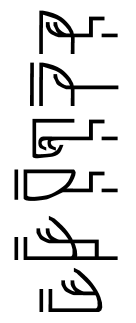

There are five basic consonant symbols, each corresponding to a group of consonants considered to be related, typically due to similarities in pronunciation. Combined with a circular Diacritical Mark, or accent symbol, there are a total of eight consonant groups consisting of anywhere from one to five variations. These variations and their Romanized letters are shown in figure 1. The romanization is how the language is represented for speakers of languages that use the roman alphabet, like English. Romanized letters convert the text and therefore aren’t necessarily pronounced like they are in English. Instead, the Spiròt romanization is an approximation of the pronunciation, given that some Spiròt characters do not directly translate to standard English pronunciations.

There are five basic consonant symbols, each corresponding to a group of consonants considered to be related, typically due to similarities in pronunciation. Combined with a circular Diacritical Mark, or accent symbol, there are a total of eight consonant groups consisting of anywhere from one to five variations. These variations and their Romanized letters are shown in figure 1. The romanization is how the language is represented for speakers of languages that use the roman alphabet, like English. Romanized letters convert the text and therefore aren’t necessarily pronounced like they are in English. Instead, the Spiròt romanization is an approximation of the pronunciation, given that some Spiròt characters do not directly translate to standard English pronunciations.

The variations on the consonants come in five varieties, each of which is formed by adding or removing Strokes from the base character. These changes each correspond to characters of a certain type of pronunciation, like plosives, fricatives, etc. Exactly what these terms mean will be covered in an article on pronunciation, but they must also be mentioned here, since the language is featural. For now, readers may simply consider them names for each of the rows of characters in figure 1. Therefore, doubling the first stroke results in plosive characters (2nd row). This added stroke is therefore called the plosive stroke. Likewise, doubling the hooked stroke results in fricative characters (3rd row) and the added stroke is called the fricative stroke. If both are doubled then the character represents an affricate (4th row), a combination of the two, while omitting the first stroke makes the character a nasal (last row). Note that two groups of variations, namely those that have the plosive stroke, have two different romanizations. These characters are pronounced differently in different situations, even though the Spiròt character remains unchanged, thus leading to two different romanizations, depending on context. These circumstances are further explored in the article on pronunciation rules for words.

The variations on the consonants come in five varieties, each of which is formed by adding or removing Strokes from the base character. These changes each correspond to characters of a certain type of pronunciation, like plosives, fricatives, etc. Exactly what these terms mean will be covered in an article on pronunciation, but they must also be mentioned here, since the language is featural. For now, readers may simply consider them names for each of the rows of characters in figure 1. Therefore, doubling the first stroke results in plosive characters (2nd row). This added stroke is therefore called the plosive stroke. Likewise, doubling the hooked stroke results in fricative characters (3rd row) and the added stroke is called the fricative stroke. If both are doubled then the character represents an affricate (4th row), a combination of the two, while omitting the first stroke makes the character a nasal (last row). Note that two groups of variations, namely those that have the plosive stroke, have two different romanizations. These characters are pronounced differently in different situations, even though the Spiròt character remains unchanged, thus leading to two different romanizations, depending on context. These circumstances are further explored in the article on pronunciation rules for words.

|

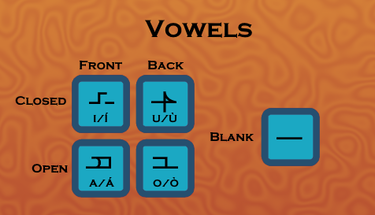

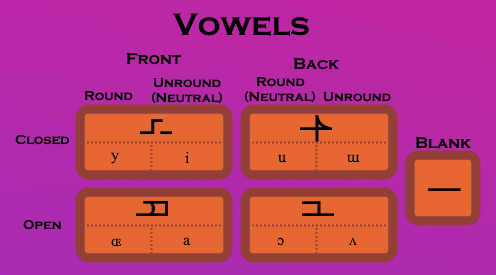

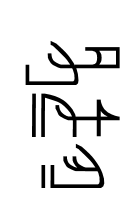

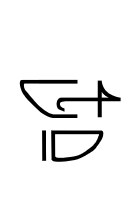

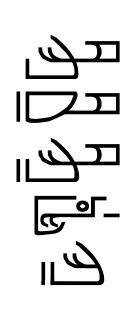

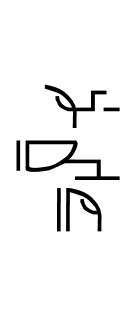

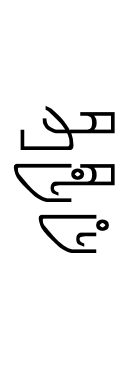

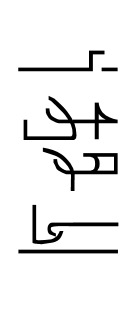

The vowels of the Spiròt language are much simpler than the consonants. There are five vowels in total (fig. 2), four that are pronounced and one that is silent, called the Blank Vowel. When a blank vowel is attached to a consonant, that consonant and the one that follows it are spoken back to back, without any vowel sound in between. The four pronounced vowels are labelled according to their pronunciation. Like the consonants, for now readers may simply consider these names for the vowels (ie. the 'a' vowel is an open-front vowel).

|

Similar to some of the consonants, the four regular vowels have two different pronunciations depending on the context. These two pronunciations are written differently in the romanization, one with and one without an accent. Exactly how consonants affect vowel pronunciations will be covered in the article on pronunciation rules for words.

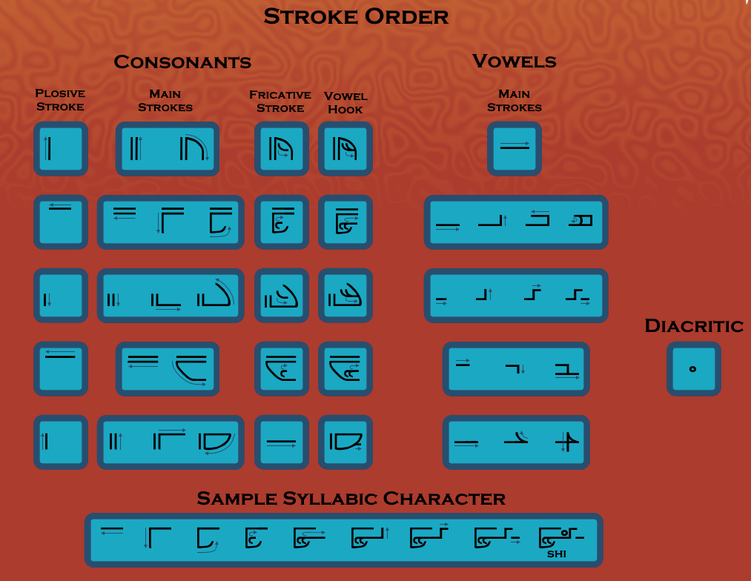

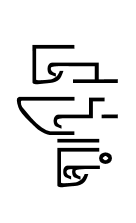

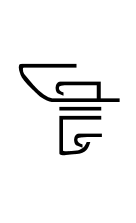

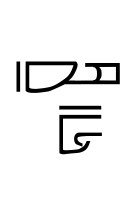

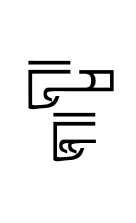

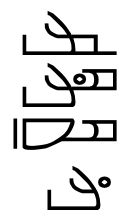

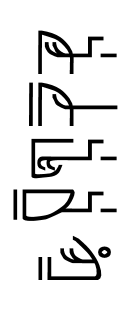

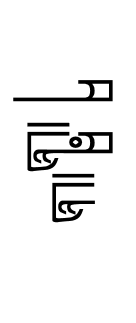

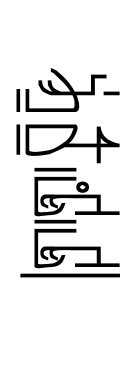

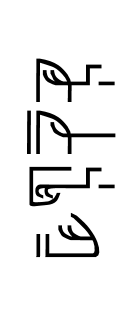

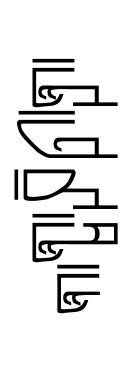

When writing a character, the consonant is written first and then connected to the vowel, if there is one. Since certain features of the consonants are modified for different pronunciations, and since vowels are connected to their consonants, each character has a particular Stroke Order. The stroke order simply indicates the order in which each line is drawn when writing a character. The stroke orders are summarized in figure 3 for each character type.

Broadly speaking, the strokes for any given character are as follows:

- the first stroke, which is doubled for plosives and affricates and omitted for nasals

- the remaining main strokes

- the vowel hook, which is doubled for fricatives and affricates

- the vowel, which is connected to the vowel hook

- the diacritic, if there is one

ARTICLE II: WORDS

|

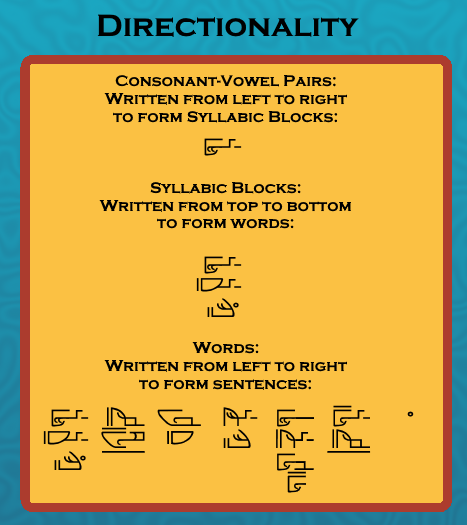

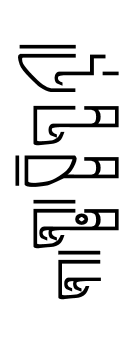

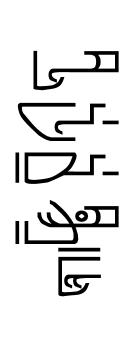

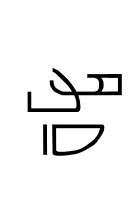

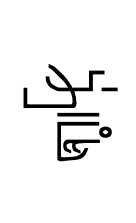

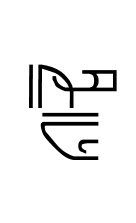

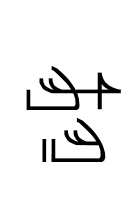

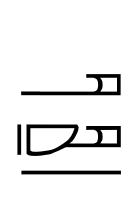

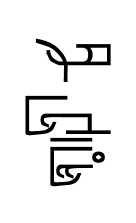

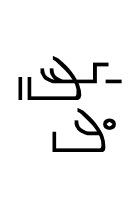

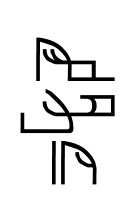

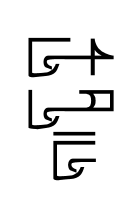

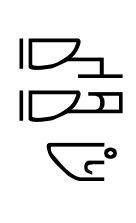

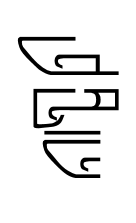

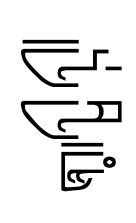

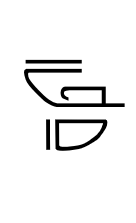

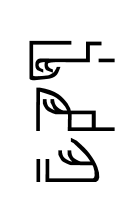

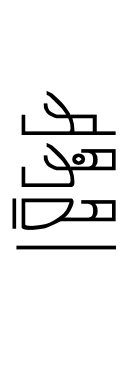

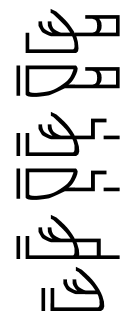

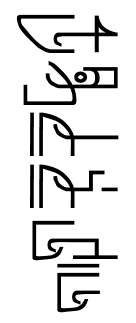

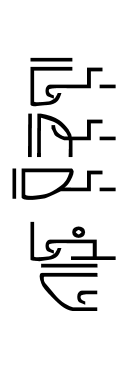

In Spiròt, the basic units of words are syllabic blocks, or characters. The basic components of these characters are the consonant and the vowel, which are written together from left to right. Words are constructed from a series of these syllabic characters written from top to bottom and sentences are made up of words written from left to right and ending with a small circle, similar to a period (fig. 1).

As a general rule, no consonant is written without a vowel, save for the last consonant in a word. In practice, however, there are some words for which the pronunciation has two consonant sounds back to back, with no vowel sound between them. Furthermore, there are words that end or begin with a vowel sound. In such cases, there are a set of rules for writing such words to help maintain the proper syllabic structure of the word. |

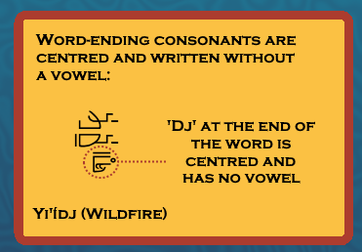

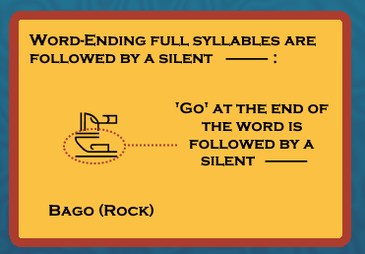

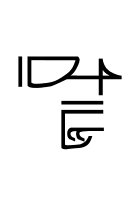

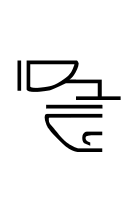

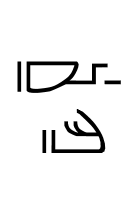

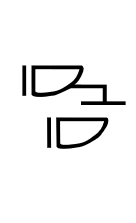

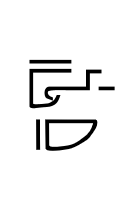

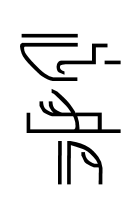

Firstly, many words in Spiròt end in a consonant. These consonants are written without a vowel and are centred compared to the other syllables in the word (fig. 2). When a word instead ends in a vowel sound, the last syllable is followed by a centred ‘h’ consonant, a horizontal line, which is silent (fig. 3).

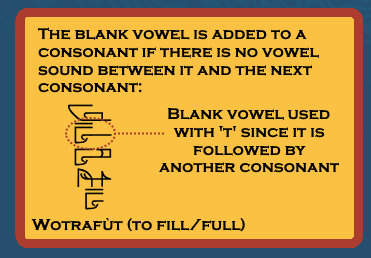

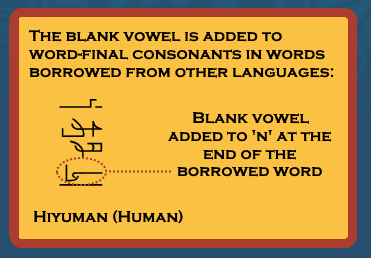

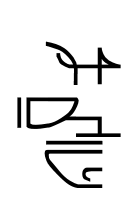

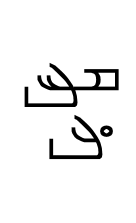

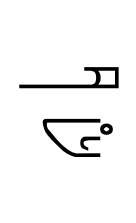

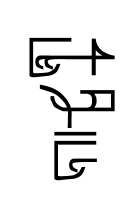

Secondly, when a consonant is written with a blank vowel, that consonant and the one that follows it are pronounced back to back (fig. 4). The blank vowel is also used in borrowed words that end in a consonant sound. In this case, the blank vowel is attached to the word-final consonant, and is followed by a word-ending ‘h’, a combination of the previous two rules (fig. 5).

|

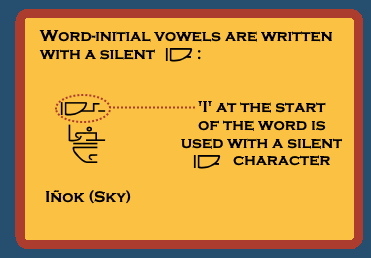

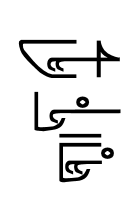

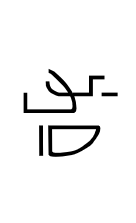

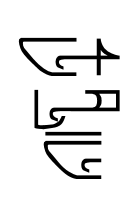

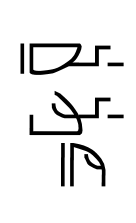

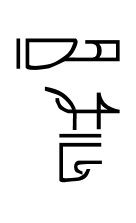

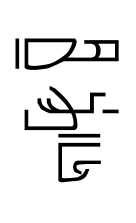

The third rule for how words are written relates to words that begin with a vowel sound. Generally, words are expected to begin with consonants. In cases where they don’t, a silent consonant character is attached to the word-initial vowel. This character is not pronounced and thus is only used to maintain the syllabic structure of the word-initial character (fig. 6). |

|

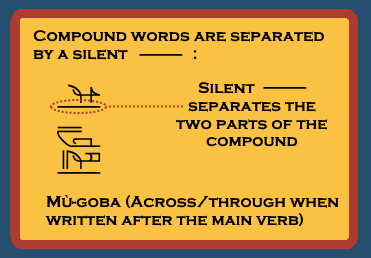

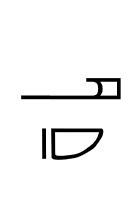

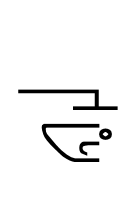

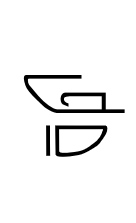

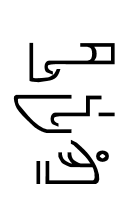

Lastly, in the special case of compound words, which are typically reserved for complex post-positions/case markers, which will be discussed in an article on grammar, the silent ‘h’ character is used again. In this case, the silent ‘h’ separates the two components of the compound (fig. 7). |

There are many other rules for the Spiròt language, but they are more closely related to pronunciation and grammar than to the writing system itself, and are thus covered in those sections.

SECTION I SUMMARY

SECTION I DEFINITIONS

Featural Writing System: A writing system that notates the building blocks of the speech sounds that make up the language. For example, all sounds pronounced with the lips may have some element in common. (Source)

Syllabic Alphabet: A writing system in which the main element is the syllable, but where syllables are built from characters representing consonants and vowels. This term is often synonymous with the term abugida, however a distinction has been made here, since consonants in abugidas usually have an inherent vowel, while in Spiròt they do not. (Source)

Consonant: A speech sound pronounced by stopping the air from flowing easily through the mouth, for example by closing the lips or touching the teeth with the tongue. (Source)

Vowel: A speech sound pronounced when the breath flows out of the mouth without being blocked by the teeth, tongue or lips. (Source)

Syllabic Character: In Spiròt, a written character comprised of a connected consonant and vowel.

Diacritical Mark: A mark, point, or sign attached to a letter or character to distinguish it from a similar character, to indicate a particular phonetic value, stress, etc. (Source)

Romanize: To convert a language's text into the roman alphabet. (Source)

Stroke: In typography, a stroke is simply one of the lines that forms a letter. (Source)

Stroke Order: The standard sequence in which a character is written, often in reference to characters in Chinese, Japanese or Korean writing. (Source) Unlike in these examples, in Spiròt, stroke order is primarily used to help determine which strokes are doubled or removed from a base character, as well as to express how vowels are connected to their consonants.

Blank Vowel: In Spiròt, the blank vowel is a character added to a consonant, in the same way as other vowels, which itself has no pronunciation and is simply used when two consonant sounds are spoken back to back.

Syllabic Alphabet: A writing system in which the main element is the syllable, but where syllables are built from characters representing consonants and vowels. This term is often synonymous with the term abugida, however a distinction has been made here, since consonants in abugidas usually have an inherent vowel, while in Spiròt they do not. (Source)

Consonant: A speech sound pronounced by stopping the air from flowing easily through the mouth, for example by closing the lips or touching the teeth with the tongue. (Source)

Vowel: A speech sound pronounced when the breath flows out of the mouth without being blocked by the teeth, tongue or lips. (Source)

Syllabic Character: In Spiròt, a written character comprised of a connected consonant and vowel.

Diacritical Mark: A mark, point, or sign attached to a letter or character to distinguish it from a similar character, to indicate a particular phonetic value, stress, etc. (Source)

Romanize: To convert a language's text into the roman alphabet. (Source)

Stroke: In typography, a stroke is simply one of the lines that forms a letter. (Source)

Stroke Order: The standard sequence in which a character is written, often in reference to characters in Chinese, Japanese or Korean writing. (Source) Unlike in these examples, in Spiròt, stroke order is primarily used to help determine which strokes are doubled or removed from a base character, as well as to express how vowels are connected to their consonants.

Blank Vowel: In Spiròt, the blank vowel is a character added to a consonant, in the same way as other vowels, which itself has no pronunciation and is simply used when two consonant sounds are spoken back to back.

section 2: Pronunciation

Begin learning how to speak Spiròt by exploring pronunciation!

In this section you'll learn how to pronounce the written characters of Spiròt and how pronunciations vary depending on the structure of words. Click on the buttons below to get started.

In this section you'll learn how to pronounce the written characters of Spiròt and how pronunciations vary depending on the structure of words. Click on the buttons below to get started.

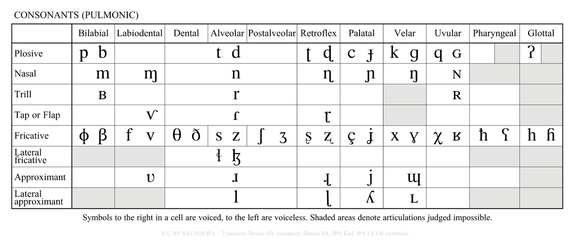

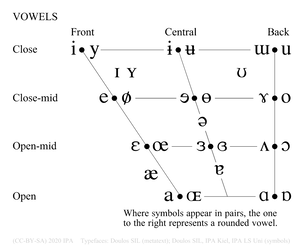

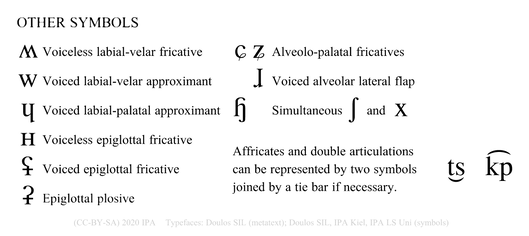

PREFACE: THE INTERNATIONAL PHONETIC ALPHABET

In order to discuss pronunciation it is important to use a standardized set of rules and sounds. The articles on pronunciation will reference the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), which provides a comprehensive list of possible sounds within any given language. Given the number and complexity of the possible sounds, the IPA has a large list of characters in a variety of categories (fig. 1, fig. 2 and fig. 3), and includes many additional diacritics and symbols. These IPA charts are arranged into a number of categories that may be unfamiliar to those who haven't seen it before. In the following articles, as the Spiròt language is discussed, explanations of the relevant terms from the IPA will also be explained.

Each symbol in the IPA generally has only one pronunciation, unlike symbols in any given language, which can have many pronunciations (ie. the 'I' in fish versus in mine) and can vary geographically (ie. regional accents). The proceeding articles will classify the sounds of the Spiròt language according to their IPA counterparts. For audio references on how these sounds are pronounced, check out the interactive IPA charts on the official International Phonetic Association website linked in the citation below.

All IPA Chart Images acquired from:

"IPA Chart, http://www.internationalphoneticassociation.org/content/ipa-chart, available under a Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 3.0 Unported License. Copyright © 2018 International Phonetic Association."

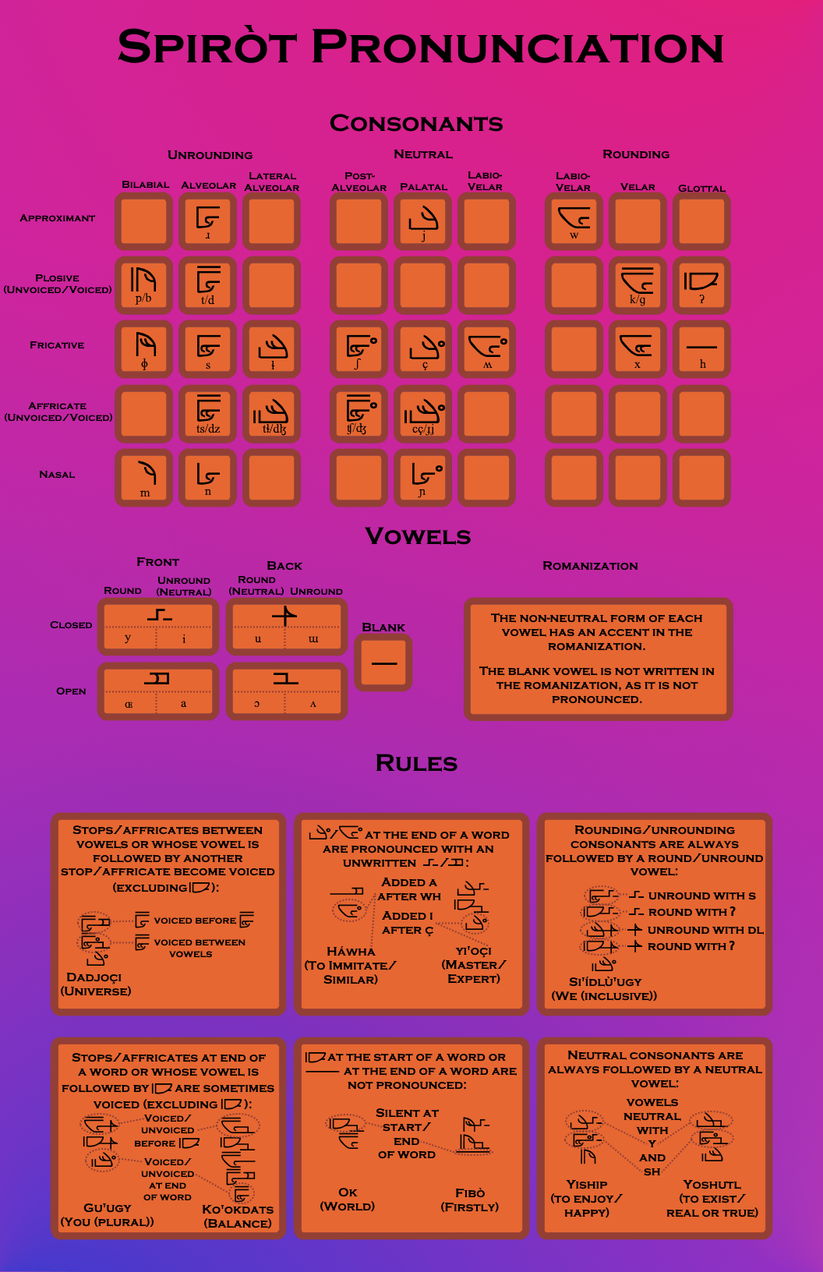

ARTICLE I: PRONUNCIATION OF THE CHARACTERS

Figure 1 shows the vowels and their phonetic pronunciations. Notice that each vowel has two pronunciations, one labelled 'round' and one labelled 'unround'. These terms correspond to the equivalent terms in the IPA, and refer to the shape of the mouth/lips. Thus, Round Vowels are pronounced with rounded lips, like the ‘o’ in ‘lobe’, while Unround Vowels are pronounced without rounding the lips, like the ‘a’ in ‘late’.

The vowels are also classified into front/back, corresponding to the position of the tongue, and open/closed, corresponding to the position of the jaw. The difference in front and back vowels can be seen in the 'ee' sound in 'feel', where the tongue is in the front, versus the 'oo' sound in 'loom', where the tongue is in the back. Similarly, the difference in open and closed vowels can be seen in the 'oo' sound in 'loom', where the mouth is nearly closed, versus the 'a' in 'father', where the mouth is wide open. In Spiròt, each vowel has a Neutral pronunciation and an alternative pronunciation that occurs depending on which consonant the vowel is attached to.

Figure 2 shows a list of consonants with their respective IPA pronunciations. Given that Spiròt is a featural language, the consonants fall into categories that roughly coincide with both the place (columns) and manner (rows) of articulation, similar to the IPA consonant chart in the preface. The Place of Articulation relates to where within the vocal tract the sound is produced while the Manner of Articulation refers to how the sound is produced. The list in figure 2 also organizes consonants into rounding, unrounding or neutral, corresponding to how they affect attached vowels.

Each manner of articulation corresponds to a specific change in the base Spiròt character. Those changes, along with the type of sound they produce and some examples from English, are summarized below:

Notice that the fricative row has three exceptions to these rules. The first two, the palatal and labio-velar fricatives, are written as base characters with an accent symbol instead of as fricatives. The glottal fricative, on the other hand, is written as a simple horizontal line. This symbol is typically silent, though not always, and therefore shares its shape with the blank vowel, which is always silent.

The places of articulation, moving from left to right in figure 2, roughly correspond to the eight base characters, with some exceptions. A summary of the characters in each column and the manners of articulation that they correspond to are listed below:

Note that the term lateral is actually a manner of articulation. However, due to the way that the Spiròt language classifies laterals, it is easier to list them as a separate column in figure 2.

Finally, there is one more aspect of pronunciation to discuss, which is voicing. A consonant is Voiced when the vocal chords are used to make the sound, while Voiceless, or unvoiced, consonants do not use the vocal chords. To see the difference, hold your hand to your throat to feel the vibrations of your vocal chords and make an ‘s’ sound, like hissing. Afterwards, do the same with the letter ‘z’ and notice that the throat vibrates with ‘z’ but not with ‘s’. That means that ‘z’ is voiced while ‘s’ is voiceless. There are many other examples of voiceless and voiced pairs, like ‘p’ and ‘b’, ‘k’ and ‘g’ or ‘f’ and ‘v’.

In figure 2, both the stops and the affricates have two pronunciations, one voiceless and one voiced. This is only a difference in pronunciation, while the written character is the same for both. Whether the character is pronounced voiceless or voiced varies depending on the word and the surrounding characters.

Each manner of articulation corresponds to a specific change in the base Spiròt character. Those changes, along with the type of sound they produce and some examples from English, are summarized below:

- Base Characters: Approximants, consonants whose pronunciation is between a consonant and a vowel, such as the ‘y’ in ‘yak’ or ‘r’ in ‘rug’.

- Double First Stroke: Plosives, sounds where airflow in the mouth is blocked and subsequently released, such as the ‘p’ in ‘punch’ or the ‘k’ in ‘kick’.

- Double Vowel Hook: Fricatives, sound where airflow is allowed to pass through a small opening, such as the ‘f’ in ‘fish’ or the ‘h’ in ‘hand’.

- Double Both: Affricates, sounds that start as a plosive and end as a fricative, such as the ‘ch’ in ‘chin’ or the ‘j’ in ‘jog’.

- Omit First Stroke: Nasal, sounds where airflow passes through the nose, such as the ‘n’ in ‘nice’ or the ‘m’ in ‘mean’.

Notice that the fricative row has three exceptions to these rules. The first two, the palatal and labio-velar fricatives, are written as base characters with an accent symbol instead of as fricatives. The glottal fricative, on the other hand, is written as a simple horizontal line. This symbol is typically silent, though not always, and therefore shares its shape with the blank vowel, which is always silent.

The places of articulation, moving from left to right in figure 2, roughly correspond to the eight base characters, with some exceptions. A summary of the characters in each column and the manners of articulation that they correspond to are listed below:

- Column 1: Bilabial Sounds, pronounced using both lips, such as the ‘p’ in ‘part’ or the ‘m’ in ‘make’, are all variations of the same character.

- Column 2: Alveolar Sounds, pronounced with the tongue against the region just above the back of the teeth, such as the ‘t’ in ‘ten’ or the ‘n’ in ‘nine’, are all variations on the same character.

- Column 3: Lateral alveolar sounds, produced by allowing airflow to pass through the sides of the tongue, such as the 'l' in 'land', are both variations of the same character.

- Column 4: Post-Alveolar Sounds, pronounced further back than alveolar sounds, such as the ‘sh’ in 'ship' and the ‘ch’ in 'chair', are written with the same character as column 2, with an added diacritic.

- Column 5: Palatal Sounds, produced with the tongue and the roof of the mouth, such as the ‘y’ in ‘yarn’, are written with various characters. The approximant shares its character with column 3, while the fricative and affricate have added diacritics. Lastly, the nasal comes from the character in column 2 with an added diacritic.

- Columns 6 and 7: Labio-Velar Sounds, pronounced with both the lips and the back of the mouth, like the ‘w’ sound in 'wind', are both written as a base character, one with and the other without a diacritic.

- Column 8: Velar Sounds, pronounced at the back of the mouth, like the ‘k’ in king or the ‘ng’ in 'running', share their character with column 7.

- Column 8: Glottal Sounds, produced near the vocal chords in the throat, like the ‘h’ sound in hot or the interruption in the word uh-oh, each have a unique character.

Note that the term lateral is actually a manner of articulation. However, due to the way that the Spiròt language classifies laterals, it is easier to list them as a separate column in figure 2.

Finally, there is one more aspect of pronunciation to discuss, which is voicing. A consonant is Voiced when the vocal chords are used to make the sound, while Voiceless, or unvoiced, consonants do not use the vocal chords. To see the difference, hold your hand to your throat to feel the vibrations of your vocal chords and make an ‘s’ sound, like hissing. Afterwards, do the same with the letter ‘z’ and notice that the throat vibrates with ‘z’ but not with ‘s’. That means that ‘z’ is voiced while ‘s’ is voiceless. There are many other examples of voiceless and voiced pairs, like ‘p’ and ‘b’, ‘k’ and ‘g’ or ‘f’ and ‘v’.

In figure 2, both the stops and the affricates have two pronunciations, one voiceless and one voiced. This is only a difference in pronunciation, while the written character is the same for both. Whether the character is pronounced voiceless or voiced varies depending on the word and the surrounding characters.

ARTICLE II: PRONUNCIATION RULES FOR WORDS

In the following discussion, the default state of all consonants is voiceless and the default state of all vowels is neutral. The rules for pronunciation will therefore explain the exceptions.

|

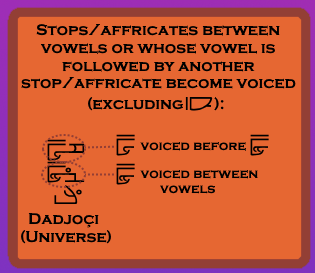

The first two rules describe when stops and affricates are voiced. Firstly, when a stop/affricate is between two vowels, or when the next consonant is another stop/affricate, it is always voiced, as is shown in the romanizations in figure 1. This excludes the glottal stop, both in terms of becoming voiced, as the glottal stop is never voiced, and in terms of causing voicing, as per the next rule. It also excludes situations where two stops are spoken together, without a vowel in between.

|

|

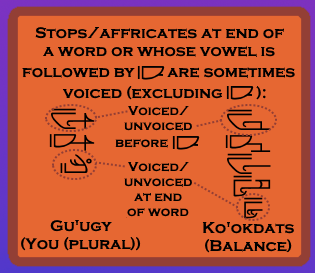

The second rule (figure 2) states that stops/affricates at the end of a word or that are followed by a glottal stop, are sometimes voiced. The behaviour of stops/affricates in these circumstances can be somewhat unpredictable, especially at the beginning and end of words, or when two such sounds occur without a vowel sound between them. In these cases, the proper pronunciation must usually be memorized. |

|

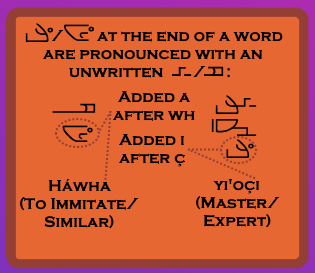

Thirdly, two characters are pronounced with an unwritten vowel at the end of a word. These two characters are the palatal and labio-velar fricative, romanized as ‘ç’ and ‘wh’ (figure 3). Specifically, ‘ç’ is pronounced with an unwritten 'i' sound while ‘wh’ is pronounced with an unwritten 'a'. These unwritten vowels are always pronounced in their neutral form and occur only at the end of a word. Otherwise, when these consonants are written, they are written with vowels, even if the written vowel is one of these sounds. Note that these vowels are included in the romanization, but not in written Spiròt. |

|

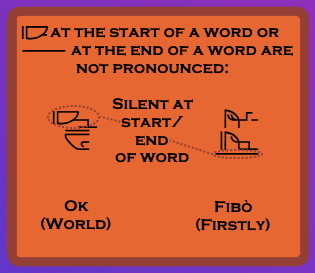

The fourth rule concerns unpronounced consonants. When the glottal stop character occurs at the start of a word or the glottal fricative occurs at the end of the word, they are not pronounced (figure 4). This is somewhat similar to the English name ‘Sarah’, which has an unpronounced ‘h’ at the end. |

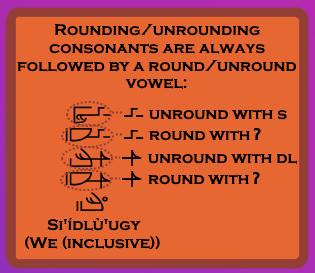

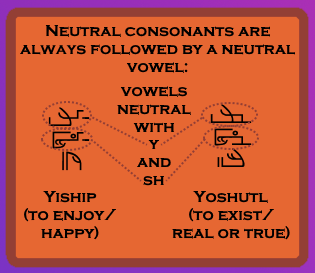

The last two rules (figures 5 and 6) both have to do with how consonants affect the rounding/unrounding of vowels. Simply put, vowels connected to unrounding consonants are always unrounded while vowels connected to rounding consonants are always rounded. Meanwhile, vowels connected to neutral consonants are always neutral. Which consonants fall into each category is shown in a figure in article 1 of this section.

SECTION II SUMMARY

SECTION II DEFINITIONS

International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA): A phonetic notation system that uses a set of symbols to represent each distinct sound that exists in human spoken language. (Source)

Rounded Vowel: A vowel pronounced with rounded lips. (Source)

Unrounded Vowel: A vowel pronounced without rounding the lips. (Source)

Neutral Pronunciation: In Spiròt, the default pronunciation of a vowel, unrounded for front vowels and rounded for back vowels.

Place of Articulation: The location where two speech organs approach or meet to produce a speech sound. (Source)

Manner of Articulation: The degree and/or type of obstruction imposed upon the air flow to produce a speech sound. (Source)

Approximant: In phonetics, a sound produced by bringing two speech organs together without causing audible friction (without direct contact). Also known as semivowels or glides (eg. r, w or y in English). (Source)

Plosive Consonant: In phonetics, a consonant sound produced by creating a momentary blockage somewhere along the oral cavity. Also known as stops (eg. p, b, t, d, k or g in English). (Source)

Fricative Consonant: In phonetics, a consonant sound produced by moving the mouth to block airflow, but not making a complete closure, allowing the air to generate audible friction (eg. f, v, s or z in English). (Source)

Affricate Consonant: In phonetics, a consonant sound that begins as a plosive and concludes with a fricative. Also known as a semiplosive (eg. ch or j in English). (Source)

Nasal Consonant: In phonetics, a sound produced when the airstream passes through the nose (eg. n, m and ng in English). (Source)

Lateral Consonant: In phonetics, a consonant sound produced by raising the tip of the tongue against the roof of the mouth to allow airflow to the sides of the tongue (eg. l in English). (Source)

Bilabial Sound: Sound produced with both lips close together or touching (eg. p, b and m in English). (Source)

Alveolar Sound: Sound produced with the tongue near or touching the alveolar ridge (behind the teeth) (eg. t, s and n in English). (Source)

Post-Alveolar Sound: Sound produced with the tongue near or touching the back of the alveolar ridge (eg. sh or ch in English). (Source)

Velar Sound: Sound produced with the back of the tongue against the velum (back part of the roof of the mouth) (eg. k, g or ng in English). (Source)

Labio-Velar Sound: Sound produced using both the lips and the velum. Sometimes also referred to as Labial-Velar, though these terms often have slightly different meanings (eg. w in English). (Source)

Glottal Sound: Sound produced using the glottis, the opening between the vocal chords (eg. h in English). (Source)

Voiced Consonant: Consonant sound produced by vibration of the vocal chords (eg. g, d, v and z in English). (Source)

Voiceless Consonant: Consonant sound produced without vibration of the vocal chords (eg. k, t, f and s in English). (Source)

Rounded Vowel: A vowel pronounced with rounded lips. (Source)

Unrounded Vowel: A vowel pronounced without rounding the lips. (Source)

Neutral Pronunciation: In Spiròt, the default pronunciation of a vowel, unrounded for front vowels and rounded for back vowels.

Place of Articulation: The location where two speech organs approach or meet to produce a speech sound. (Source)

Manner of Articulation: The degree and/or type of obstruction imposed upon the air flow to produce a speech sound. (Source)

Approximant: In phonetics, a sound produced by bringing two speech organs together without causing audible friction (without direct contact). Also known as semivowels or glides (eg. r, w or y in English). (Source)

Plosive Consonant: In phonetics, a consonant sound produced by creating a momentary blockage somewhere along the oral cavity. Also known as stops (eg. p, b, t, d, k or g in English). (Source)

Fricative Consonant: In phonetics, a consonant sound produced by moving the mouth to block airflow, but not making a complete closure, allowing the air to generate audible friction (eg. f, v, s or z in English). (Source)

Affricate Consonant: In phonetics, a consonant sound that begins as a plosive and concludes with a fricative. Also known as a semiplosive (eg. ch or j in English). (Source)

Nasal Consonant: In phonetics, a sound produced when the airstream passes through the nose (eg. n, m and ng in English). (Source)

Lateral Consonant: In phonetics, a consonant sound produced by raising the tip of the tongue against the roof of the mouth to allow airflow to the sides of the tongue (eg. l in English). (Source)

Bilabial Sound: Sound produced with both lips close together or touching (eg. p, b and m in English). (Source)

Alveolar Sound: Sound produced with the tongue near or touching the alveolar ridge (behind the teeth) (eg. t, s and n in English). (Source)

Post-Alveolar Sound: Sound produced with the tongue near or touching the back of the alveolar ridge (eg. sh or ch in English). (Source)

Velar Sound: Sound produced with the back of the tongue against the velum (back part of the roof of the mouth) (eg. k, g or ng in English). (Source)

Labio-Velar Sound: Sound produced using both the lips and the velum. Sometimes also referred to as Labial-Velar, though these terms often have slightly different meanings (eg. w in English). (Source)

Glottal Sound: Sound produced using the glottis, the opening between the vocal chords (eg. h in English). (Source)

Voiced Consonant: Consonant sound produced by vibration of the vocal chords (eg. g, d, v and z in English). (Source)

Voiceless Consonant: Consonant sound produced without vibration of the vocal chords (eg. k, t, f and s in English). (Source)

SECTION II SUPPLEMENT: ACCENTS

The articles on pronunciation are based upon the classical, or standard, Spiròt accent. This is the accent taught to most humans (unless they learn directly from Spiròts) and is also the accent believed to have been spoken by the ancient spiròts. In the modern era, however, each of the four spiròt tribes has their own accent.

These accents are not reflected in the written language but are written in the romanization, as the romanization is meant to convey the pronunciation. Therefore, spiròts' names and words spoken by different types of spiròts may have romanizations that don't exactly follow the rules presented in the other parts of this section. A summary of how pronunciation differs among the different types of spiròts is presented below.

Note: The more subtle aspects of these accents (specifically, aspiration and ejectives) are not easily reproduced via the tool used to produce AI sound files. Nevertheless, I've included two words with approximate AI pronunciations (similar to the vocab section) in each of the accents, to give some sense of the changes in pronunciation. If you'd like to hear what aspirated or ejective consonants actually sound like, I recommend visiting the Glossika Phonics Youtube channel and searching 'aspirated' or 'ejective'. Plus, they have a lot of other phonetic sound samples too!

These accents are not reflected in the written language but are written in the romanization, as the romanization is meant to convey the pronunciation. Therefore, spiròts' names and words spoken by different types of spiròts may have romanizations that don't exactly follow the rules presented in the other parts of this section. A summary of how pronunciation differs among the different types of spiròts is presented below.

- Harsh sounds (such as stops and affricates) between vowels tend to be weakened (a process known as lenition in linguistics) by fire and air spiròts.

- Conversely, earth and water spiròts tend to produce harsher sounds (a process called fortition in linguistics) at the beginning and end of words.

- Stops and affricates after glottal stops tend to become voiceless (a process known as devoicing) when spoken by earth and fire spiròts, and also take on a glottal characteristic, becoming ejectives (ejectives are written with a ' after the consonant).

- Finally, air and water spiròts devoice and aspirate their stops and affricates at the beginning and end of words (aspiration involves an additional exhalation after the sound and is written as an 'h' after the consonant). Furthermore, glottal stops in these accents are pronounced as approximants (an instance of the linguistic process of gliding), resulting in glottal stops after round vowels sounding like 'w' and glottal stops after unround vowels sounding like 'y'.

Note: The more subtle aspects of these accents (specifically, aspiration and ejectives) are not easily reproduced via the tool used to produce AI sound files. Nevertheless, I've included two words with approximate AI pronunciations (similar to the vocab section) in each of the accents, to give some sense of the changes in pronunciation. If you'd like to hear what aspirated or ejective consonants actually sound like, I recommend visiting the Glossika Phonics Youtube channel and searching 'aspirated' or 'ejective'. Plus, they have a lot of other phonetic sound samples too!

Section 3: Grammar

Continue learning how to speak Spiròt by exploring grammar!

In this section you'll learn the basics of Spiròt grammar, such as the word order, noun classes and how to use pronouns and determiners. Click on the buttons below to get started.

In this section you'll learn the basics of Spiròt grammar, such as the word order, noun classes and how to use pronouns and determiners. Click on the buttons below to get started.

ARTICLE I: BASIC WORD ORDER

The Word Order of a language describes how individual words are organized in a sentence. The basic word order can be defined by how three main parts of the sentence are arranged: the Subject, Object and Verb. The subject of a sentence is the Noun Phrase that performs the action (eg. in the sentence “The man kicked the ball,” ‘The man’ is the subject). A noun phrase can be just a noun (eg. in the sentence “Cats eat fish,” ‘Cats’ is the subject) or can consist of the noun and any Modifiers, Determiners, etc. (eg. in the sentence “The hungry cats eat fish,” ‘The hungry cats’ is the subject).

Similarly, the object of a sentence is the noun phrase that receives the action (eg. in the sentence “The man kicked the big red ball,” ‘The big red ball’ is the object). Lastly, the verb or Verb Phrase describes the action (eg. in the sentence “The cat quickly ate the fish,” ‘quickly ate’ is the verb phrase). Similar to a noun phrase, a verb phrase can just be a verb, or can be a verb and any words that modify its meaning. Theories of grammar often consider the object to be a part of the verb phrase and consider adverbs, like quickly, separately from the verb phrase, but for simplicity we will treat them as outlined above.

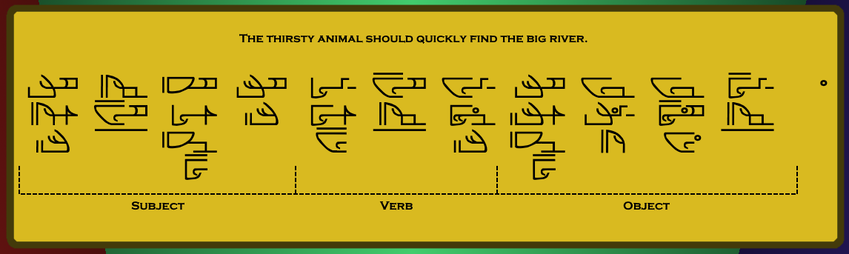

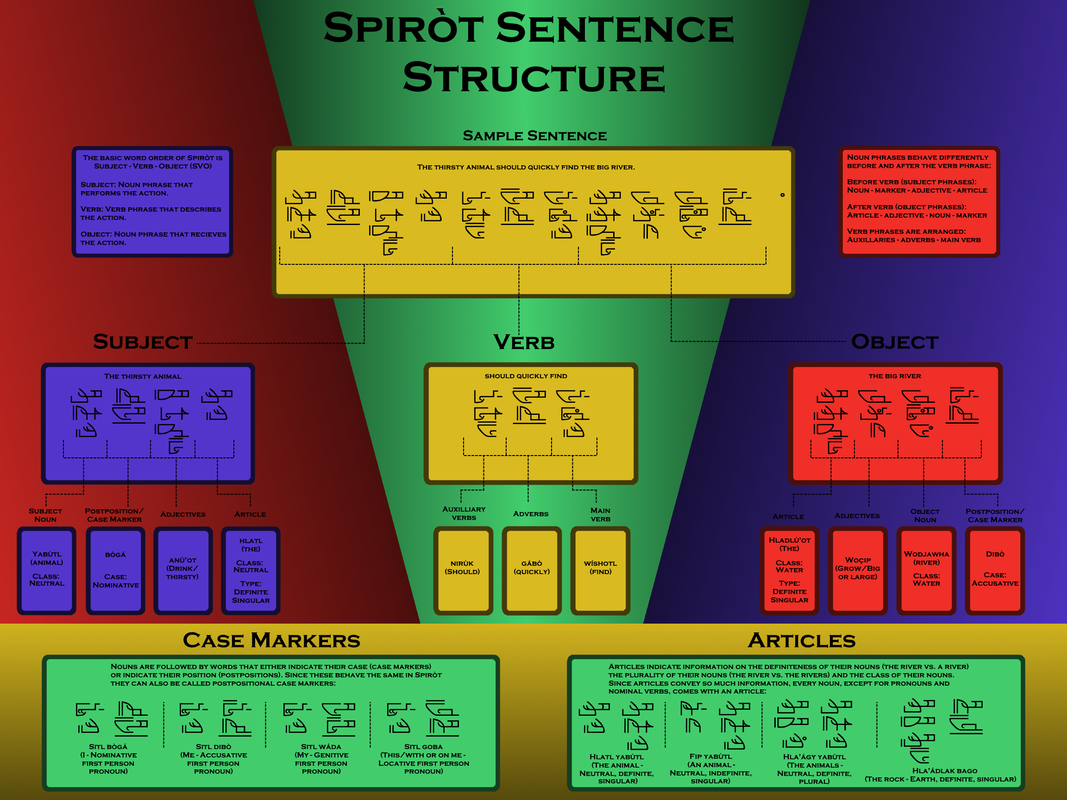

In Spiròt, the basic word order is Subject-Verb-Object (SVO). The sample sentence in figure 1 shows which parts of the sentence are the subject, verb and object. This sample sentence will be used to help explain the details of Spiròt word order. This is the same basic word order as English, but different languages arrange these in different ways (eg. SOV, VSO, OVS, etc.).

Similarly, the object of a sentence is the noun phrase that receives the action (eg. in the sentence “The man kicked the big red ball,” ‘The big red ball’ is the object). Lastly, the verb or Verb Phrase describes the action (eg. in the sentence “The cat quickly ate the fish,” ‘quickly ate’ is the verb phrase). Similar to a noun phrase, a verb phrase can just be a verb, or can be a verb and any words that modify its meaning. Theories of grammar often consider the object to be a part of the verb phrase and consider adverbs, like quickly, separately from the verb phrase, but for simplicity we will treat them as outlined above.

In Spiròt, the basic word order is Subject-Verb-Object (SVO). The sample sentence in figure 1 shows which parts of the sentence are the subject, verb and object. This sample sentence will be used to help explain the details of Spiròt word order. This is the same basic word order as English, but different languages arrange these in different ways (eg. SOV, VSO, OVS, etc.).

Beyond the basic word order, languages also have rules regarding how other parts of phrases are arranged. In noun phrases this can include determiners, which clarify the identity of the noun (eg. the, a/an, this, that, etc. in English), Adjectives, which describe the noun (eg. hungry, pretty, silly, etc. in English), Adpositions, which denote the position of the noun (eg. of, at, in, on, with, etc. in English) as well as others.

Before touching on word order within noun phrases, there are two groups of words that behave quite differently from their English counterparts. These are adpositions, which are Postpositions in Spiròt, and Articles.

Starting with postpositions, they always come directly after the noun they refer to. This contrasts with English prepositions, which come before the noun (eg. in the sentence “The cat in the house,” ‘in’ is a preposition vs. in the sentence “The cat the house in” the word ‘in’ is postpositional, though this isn’t grammatically correct in English).

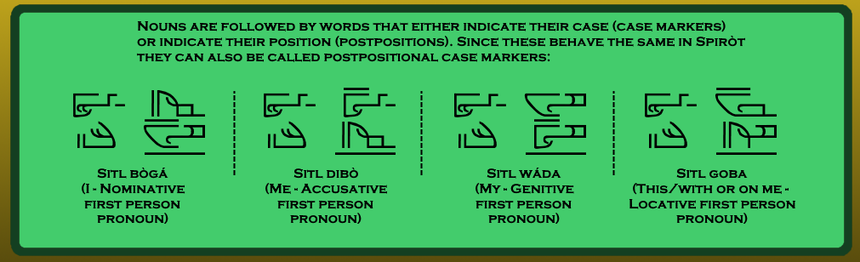

In addition, Spiròt postipositions take the role of Case Markers, which identify the case, or role, of the noun in a sentence. Many languages indicate the case of nouns, either with separate words or by modifying the noun itself. Though English doesn’t do this with standard nouns, it does do it with pronouns. For example, the first person pronoun in English changes depending on if it is the subject (Nominative Case) (eg. “I saw a fish”), object (Accusative Case) (eg. “The fish saw me”) or the owner (Genitive Case) (eg. “My fish saw a dog”). Due to their dual role in the Spiròt language, we will call these words Postpositional Case Markers, and every noun and pronoun, aside from nominal verbs in some circumstances, is followed by one. Examples of how postpositional case markers affect nouns are shown in figure 2. These are only some of the basic postpositional case markers, and there are also complex postpositional case markers which identify more specific cases and positions.

Before touching on word order within noun phrases, there are two groups of words that behave quite differently from their English counterparts. These are adpositions, which are Postpositions in Spiròt, and Articles.

Starting with postpositions, they always come directly after the noun they refer to. This contrasts with English prepositions, which come before the noun (eg. in the sentence “The cat in the house,” ‘in’ is a preposition vs. in the sentence “The cat the house in” the word ‘in’ is postpositional, though this isn’t grammatically correct in English).

In addition, Spiròt postipositions take the role of Case Markers, which identify the case, or role, of the noun in a sentence. Many languages indicate the case of nouns, either with separate words or by modifying the noun itself. Though English doesn’t do this with standard nouns, it does do it with pronouns. For example, the first person pronoun in English changes depending on if it is the subject (Nominative Case) (eg. “I saw a fish”), object (Accusative Case) (eg. “The fish saw me”) or the owner (Genitive Case) (eg. “My fish saw a dog”). Due to their dual role in the Spiròt language, we will call these words Postpositional Case Markers, and every noun and pronoun, aside from nominal verbs in some circumstances, is followed by one. Examples of how postpositional case markers affect nouns are shown in figure 2. These are only some of the basic postpositional case markers, and there are also complex postpositional case markers which identify more specific cases and positions.

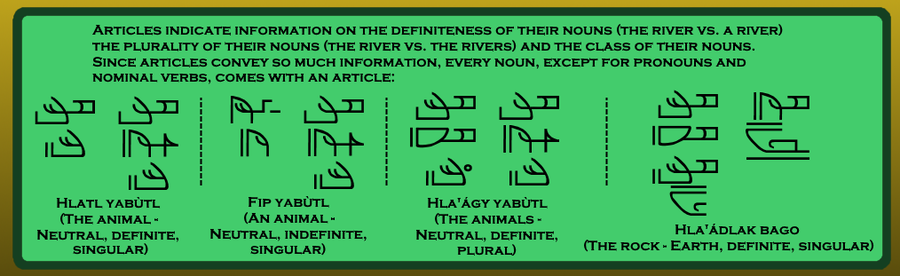

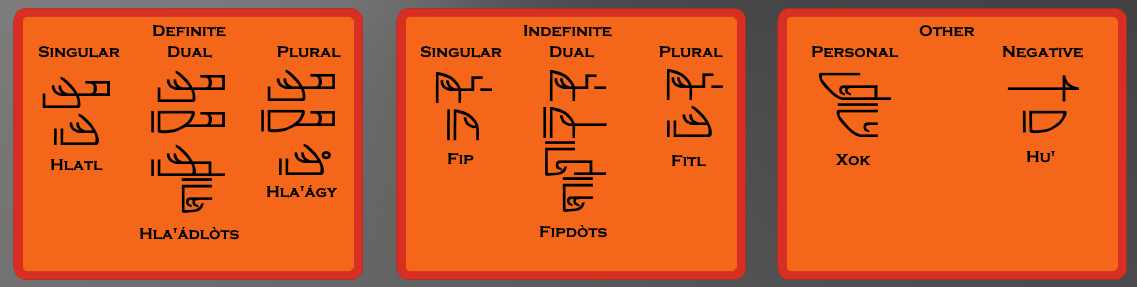

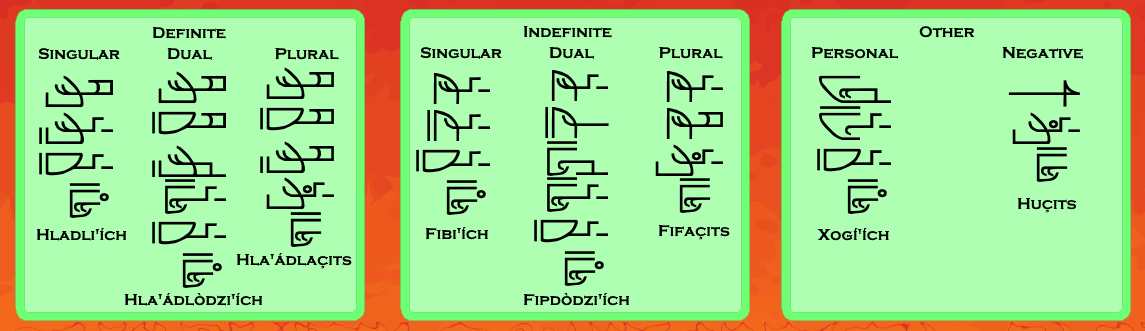

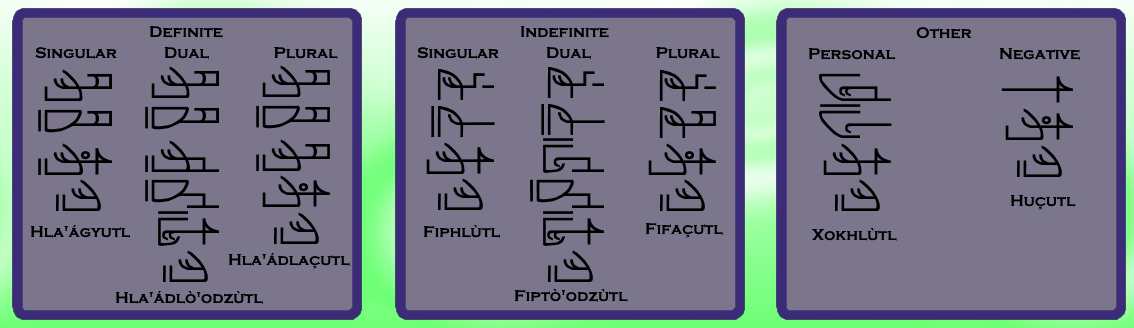

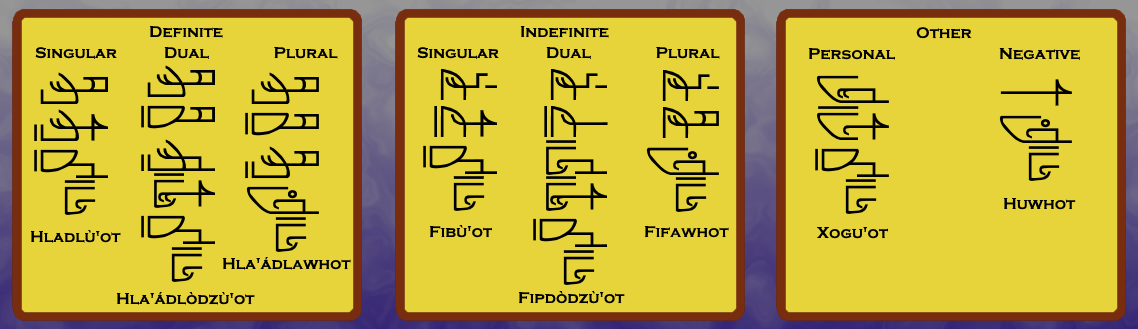

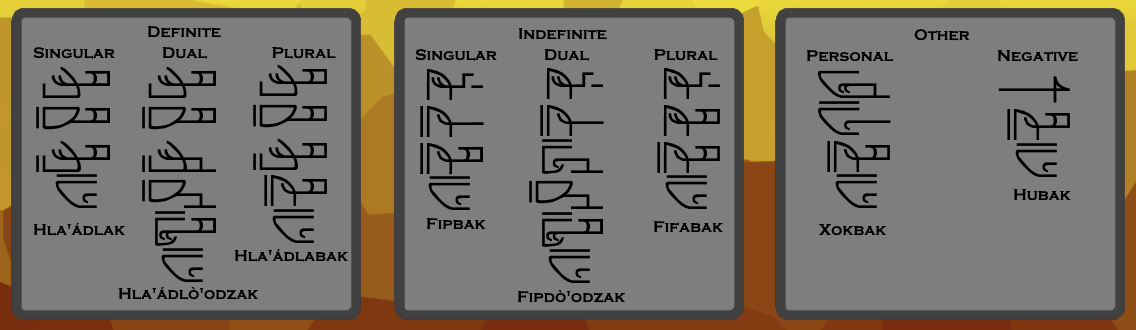

Next, unlike English articles (the, a/an), which only indicate the specificity of the noun (eg. ‘The dog’ is a specific dog, while ‘A dog’ could be any dog), Spiròt articles indicate specificity as well as Number and Noun Class. This will be discussed further in a separate article on noun class. For now, there are two important takeaways. First, Spiròt has five different noun classes: fire, air, water, earth and neutral. Every regular noun belongs to one of these classes and the article changes depending on the noun’s class. Second, plurality isn’t indicated on the noun, like in English (eg. ‘The window’ vs. ‘The windows’). Instead, it is marked on the article (in English, this might look like ‘The window’ vs. ‘Thes window’). Thus, every noun, except pronouns and nominal verbs, must be accompanied by an article. Examples of how articles change the meaning of their nouns are shown in figure 3.

|

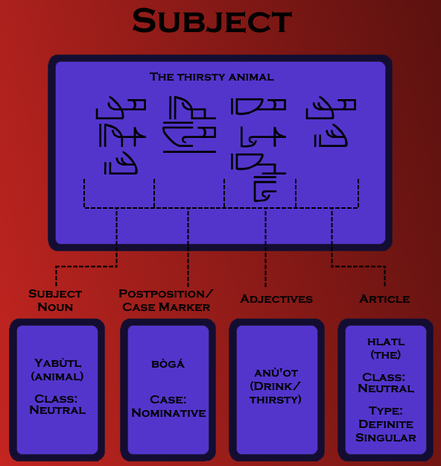

Word order within noun phrases in Spiròt is different in subject noun phrases compared to object noun phrases. We will therefore call these Subject Phrases and Object Phrases to differentiate them. The subject phrase order is noun-postposition-adjectives-article (figure 4).

|

|

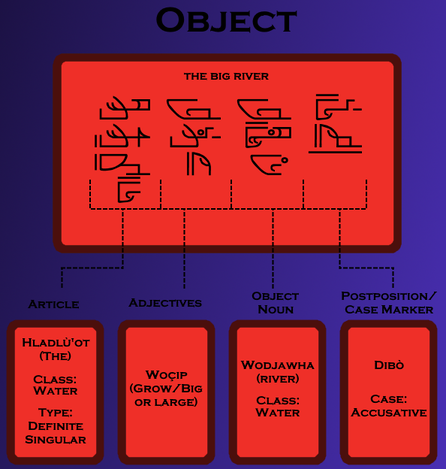

Object phrases are ordered article-adjectives-noun-postposition (figure 5), which is almost the same as English, aside from the location of the adposition. If you’re unsure about the order, think of the sentence as evolving from the verb phrase outwards (articles come first, then adjectives, then the noun-postposition pair).

|

|

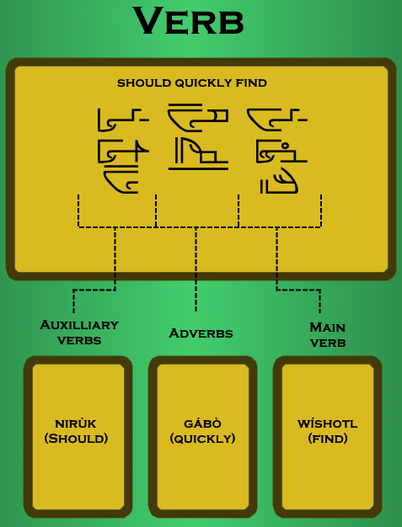

Lastly, the word order in verb phrases is much simpler. In general, the order is auxiliaries-adverbs-main verb (figure 6). Auxiliary Verbs, or simply auxiliaries, modify the meaning of the main verb (eg. in English, “I run” is a statement of fact, while “I should run” is a hope or suggestion. Should, in this case, is an auxiliary). Adverbs, on the other hand, describe the verb (eg. in the sentence “I ran quickly,” ‘quickly’ is an adverb).

|

The above only refers to simple sentences. Both noun phrases and verb phrases have further rules for more complex sentences (ie. sentences with indirect objects, multiple auxiliaries, determiners other than articles or multiple nouns in the subject and/or object phrases).

ARTICLE II: NOUN CLASS

Every Common Noun belongs to one of five noun classes. The class of a noun will dictate the class of the article used with the noun as well as the Third Person Pronoun used to refer to it. In addition, articles inform readers and speakers about the definiteness and plurality of noun. As a result, whereas English has only two basic articles (the and a/an), Spiròt has thirty different basic articles as well as a number of additional articles, each containing three pieces of information.

Spiròt has three forms of plurality: Singular, Dual and Plural. The singular and plural refer to a single instance of the noun or to multiple instances of the noun, just as in English (eg. ‘The dog’ vs. ‘The dogs’). The dual is used to refer to exactly two of something, such as ‘The two dogs’, but unlike English there is a dedicated word for ‘The two’. This is not the case for higher numbers, for which the number is added like an adjective, similar to English.

The most common forms of definiteness in Spiròt are Definite or Indefinite, meaning they refer to either a specific instance of the noun or a non-specific instance of the noun (eg. ‘The dog’ vs. ‘A dog’). Additionally, Spiròt has Negative Articles and Personal Articles. Negative articles, unlike definite and indefinite articles, indicate none of the noun (eg. ‘The dogs’ vs. ‘No dogs’). Personal articles, on the other hand, are used with personal nouns, which are the names of individuals.

Lastly, and most importantly, Spiròt has five noun classes: Neutral, Fire, Air, Water and Earth. While there are rules about what sorts of nouns belong to each class, these are more like broad guidelines than hard rules. Cultural connections between nouns may lead to unexpected classes for certain nouns (for instance, though one might expect ‘tree’ to be an earth class noun, it is actually a fire class noun due to its connection to the Prismwood, which houses the fire monolith, as well as its use as firewood). Additionally, derived words often carry the class of the noun from which they were derived, even if they meet the criteria for another class. As a result, non-native speakers may simply have to memorize the class of nouns or make educated guesses based on the form and function of those nouns. What follows are descriptions of the generalizations about each of the noun classes, which can be used to make such guesses, with the caveat that these rules may not always apply in as obvious a way as they are presented.

Spiròt has three forms of plurality: Singular, Dual and Plural. The singular and plural refer to a single instance of the noun or to multiple instances of the noun, just as in English (eg. ‘The dog’ vs. ‘The dogs’). The dual is used to refer to exactly two of something, such as ‘The two dogs’, but unlike English there is a dedicated word for ‘The two’. This is not the case for higher numbers, for which the number is added like an adjective, similar to English.

The most common forms of definiteness in Spiròt are Definite or Indefinite, meaning they refer to either a specific instance of the noun or a non-specific instance of the noun (eg. ‘The dog’ vs. ‘A dog’). Additionally, Spiròt has Negative Articles and Personal Articles. Negative articles, unlike definite and indefinite articles, indicate none of the noun (eg. ‘The dogs’ vs. ‘No dogs’). Personal articles, on the other hand, are used with personal nouns, which are the names of individuals.

Lastly, and most importantly, Spiròt has five noun classes: Neutral, Fire, Air, Water and Earth. While there are rules about what sorts of nouns belong to each class, these are more like broad guidelines than hard rules. Cultural connections between nouns may lead to unexpected classes for certain nouns (for instance, though one might expect ‘tree’ to be an earth class noun, it is actually a fire class noun due to its connection to the Prismwood, which houses the fire monolith, as well as its use as firewood). Additionally, derived words often carry the class of the noun from which they were derived, even if they meet the criteria for another class. As a result, non-native speakers may simply have to memorize the class of nouns or make educated guesses based on the form and function of those nouns. What follows are descriptions of the generalizations about each of the noun classes, which can be used to make such guesses, with the caveat that these rules may not always apply in as obvious a way as they are presented.

|

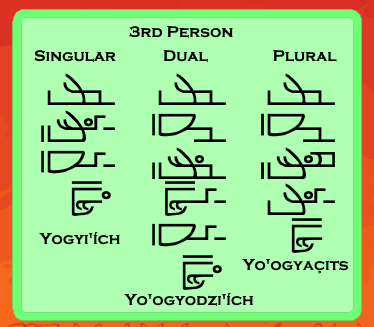

The neutral class typically applies to nouns of space and time (eg. moment, history, place, etc.), as well as to nouns that refer to broad concepts or groups (eg. a group of spiròts of mixed elements or of objects belonging to more than one class, animals (in general), plants (in general), etc.). In addition, nouns that generally lack a specific elemental association may also fall into this category (eg. humans). The neutral third person pronouns (figure 1) and neutral articles (figure 2) are the most basic forms and, if the class of a noun is uncertain or unclear, these would be the most well understood substitutes.

|

|

The fire noun class is typically reserved for nouns that relate to fire (eg. fire, spark, light, heat, etc.) as well as nouns of belief or action (eg. faith, soul, jump (as a noun), act (as a noun), etc.). The Declensions of the fire third person pronouns (figure 3) and articles (figure 4) are derived from a Suffixed ‘yich’, the Spiròt word for fire. As a result, these words generally end with a variation of the word ‘Yich’, often realized as ‘'ích’ but also sometimes as ‘çits’.

|

|

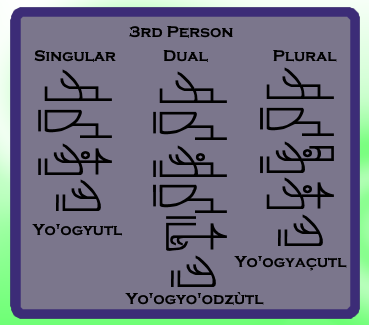

The air noun class usually contains nouns related to air (eg. wind, storm, tornado, etc.) as well as nouns of thought or discovery (eg. mind, idea, knowledge, etc.). The declensions of the air third person pronouns (figure 5) and articles (figure 6) are derived from a suffixed ‘hlùtl’, the Spiròt word for air, resulting in endings such as ‘utl’, ‘ùtl’, ‘hlùtl’ or ‘çutl’.

|

|

The water noun class typically encompasses nouns related to water (eg. river, ocean, water droplet, etc.) as well as nouns of emotion or community (eg. heart, joy, unity, etc.). The water third person pronoun (figure 7) and water article (figure 8) declensions are derived from a suffixed ‘wot’, Spiròt for water, often realized as ‘'ot’ but also sometimes as ‘whot’ at the end of the word.

|

|

Lastly, earth class nouns are usually related to earth (eg. rock, mountain, dirt, etc.) as well as nouns of physicality or physical objects without another elemental association (eg. war, fight, eye, etc.). Earth third person pronoun (figure 9) and earth article (figure 10) declensions result from a suffixed ‘bak’, the Spiròt word for earth, resulting in either a suffixed ‘bak’ or simply ‘ak’.

|

ARTICLE III: PRONOUNS AND DETERMINERS

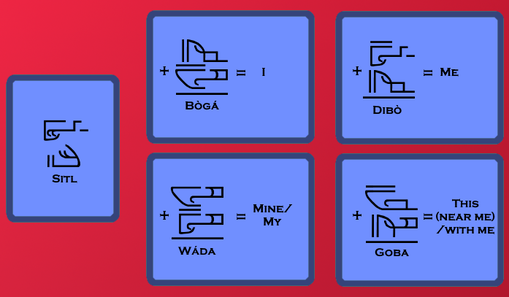

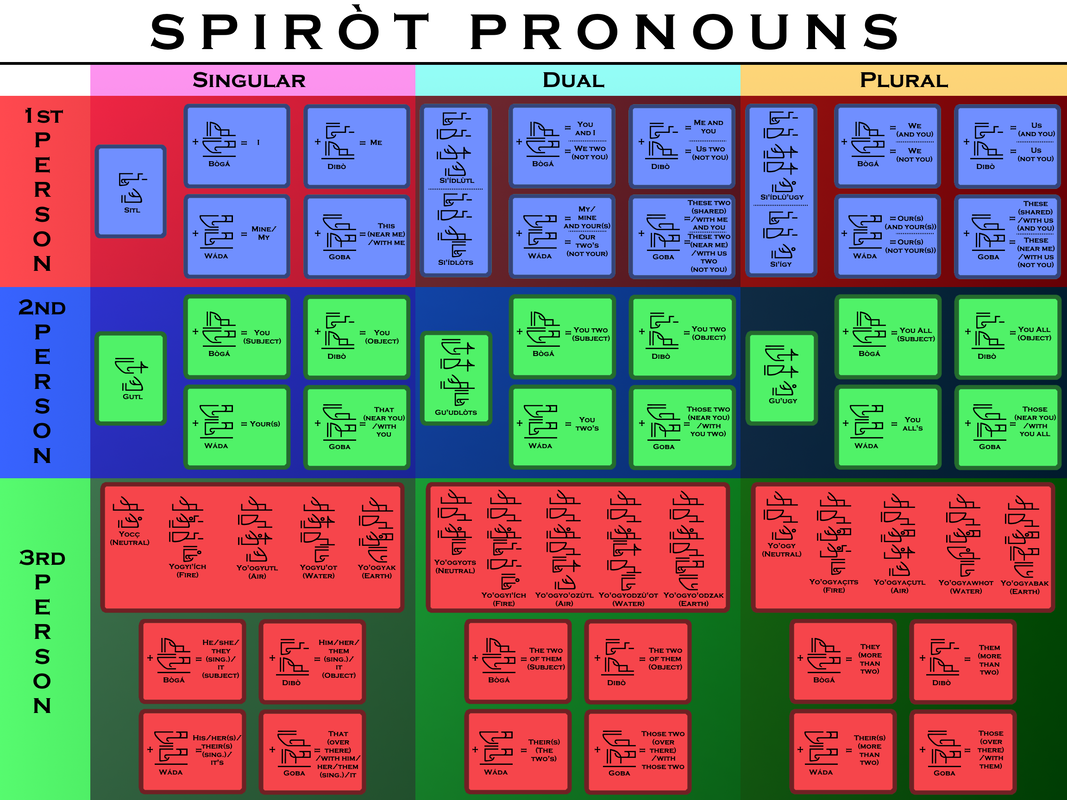

At their most basic, Pronouns are words used to refer to a noun that is either implied or has been previously mentioned. Examples of some basic pronouns in English are words such as I, you, he, her, them, mine, it, this, those, etc. In Spiròt, each combination of grammatical Person, number, and class has its own pronoun. For example, the first person singular pronoun is ‘sitl,’ which corresponds to English ‘I,’ ‘me,’ ‘mine,’ and ‘this,’ as well as the Determiner ‘my.’ Whereas English has single words for each of these, Spiròt combines two words, a pronoun and a postpositional case marker, to convey the same meaning. So, for example, ‘I’ is given by the combination ‘sitl bògá’ while ‘me’ is written as ‘sitl dibò.’

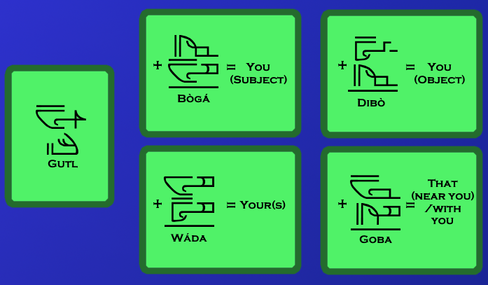

The most commonly used pronouns combine one of the basic pronoun words with one of four case markers: ‘bògá’ (nominative case), ‘dibò’ (accusative case), ‘wáda’ (genitive case), and ‘goba’ (Locative Case). Pronouns can be combined with other case markers, but they are less common and their meanings can be inferred through context.

First Person Pronouns are those pronouns that refer to the speaker and any others (I, me, we, us, etc.). The singular combinations of first person pronouns are shown in figure 1. Combining the basic pronoun, ‘sitl,’ with ‘bògá’ or ‘dibò’ results in a Personal Pronoun, either as a subject (I), when combined with ‘bògá,’ or as an object (me), when combined with ‘dibò.’ When combined with ‘wáda’ it can be used as a Possessive Pronoun (eg. That fish is mine) when on its own, or a Possessive Determiner (eg. That is my fish) when it occurs with another noun. This pattern holds for all other pronouns when combined with ‘wada,’ although there are some special cases with unique uses.

The most commonly used pronouns combine one of the basic pronoun words with one of four case markers: ‘bògá’ (nominative case), ‘dibò’ (accusative case), ‘wáda’ (genitive case), and ‘goba’ (Locative Case). Pronouns can be combined with other case markers, but they are less common and their meanings can be inferred through context.

First Person Pronouns are those pronouns that refer to the speaker and any others (I, me, we, us, etc.). The singular combinations of first person pronouns are shown in figure 1. Combining the basic pronoun, ‘sitl,’ with ‘bògá’ or ‘dibò’ results in a Personal Pronoun, either as a subject (I), when combined with ‘bògá,’ or as an object (me), when combined with ‘dibò.’ When combined with ‘wáda’ it can be used as a Possessive Pronoun (eg. That fish is mine) when on its own, or a Possessive Determiner (eg. That is my fish) when it occurs with another noun. This pattern holds for all other pronouns when combined with ‘wada,’ although there are some special cases with unique uses.

Of particular note is the meaning of the first person pronoun when combined with ‘goba.’ The Spiròt word ‘goba’ is a special case, as pronouns combined with it can have different meanings depending on context. Generally, when a ‘goba-pronoun’ occurs at the beginning of a phrase it is a Demonstrative (this, that, these, those, etc.), while if it is at the end of a phrase it is a simple locative (with or by me, with or by you, etc.). So, for example, the two meanings presented for the first person ‘goba-pronoun' in figure 1 occur in different places in a phrase (eg. ‘Sitl goba spiròt bògá hlatl’ would mean ‘This spiròt’ while ‘Spiròt bògá hlatl sitl goba’ would mean ‘The spiròt with me’). These two meanings are often similar, and even interchangeable, but not always (eg. the sentences ‘I went to the store with him’ and ‘I went to that store’ mean two different things, but in Spiròt these two sentences would only differ by the positioning of the ‘goba-pronoun’). Additionally, like the possessives, the demonstratives can be used on their own, as Demonstrative Pronouns (eg. He saw that), or along with other nouns, as Demonstrative Determiners (eg. He saw that fish). This is true of all of the pronouns when combined with ‘goba.’

Note that determiners and pronouns often overlap in language, with the key distinction being whether they replace a noun or modify a noun. So, for example, in the sentence ‘this is my cat,’ the word ‘my’ is a determiner, as it is used in conjunction with the word ‘cat,’ while in the sentence ‘This cat is mine,’ the word ‘mine’ is a pronoun because it acts as the object of the sentence, independent of any other nouns. This is true in Spiròt as well, but whereas in English the words ‘my’ and ‘mine’ are different, in Spiròt they are the same, distinguished only by the presence or absence of an additional noun.

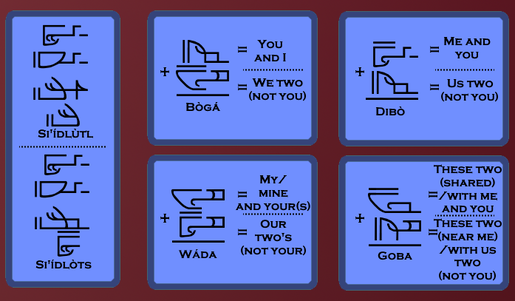

Unlike English, Spiròt also has a collection of dual pronouns, which refer to exactly two of something. Figure 2 shows the dual first person pronouns. Notice that there are two different sets of pronouns in this case, which are either Inclusive (upper words in each box in figure 2) or Exclusive (lower words in each box in figure 2). These differ based on whether the person being spoken to is included or excluded. Thus, if person A is speaking with person B while person C stands beside them, saying ‘si'ídlùtl bògá nirùk hu'ích amùt’ would mean ‘you and I should eat,’ referring to persons A and B, while ‘si'ídlòts bògá nirùk hu'ích amùt’ would mean ‘We two should eat’ referring to persons A and C. The same is true of the ‘dibò-pronouns’ and ‘wáda-pronouns.’

Note that determiners and pronouns often overlap in language, with the key distinction being whether they replace a noun or modify a noun. So, for example, in the sentence ‘this is my cat,’ the word ‘my’ is a determiner, as it is used in conjunction with the word ‘cat,’ while in the sentence ‘This cat is mine,’ the word ‘mine’ is a pronoun because it acts as the object of the sentence, independent of any other nouns. This is true in Spiròt as well, but whereas in English the words ‘my’ and ‘mine’ are different, in Spiròt they are the same, distinguished only by the presence or absence of an additional noun.

Unlike English, Spiròt also has a collection of dual pronouns, which refer to exactly two of something. Figure 2 shows the dual first person pronouns. Notice that there are two different sets of pronouns in this case, which are either Inclusive (upper words in each box in figure 2) or Exclusive (lower words in each box in figure 2). These differ based on whether the person being spoken to is included or excluded. Thus, if person A is speaking with person B while person C stands beside them, saying ‘si'ídlùtl bògá nirùk hu'ích amùt’ would mean ‘you and I should eat,’ referring to persons A and B, while ‘si'ídlòts bògá nirùk hu'ích amùt’ would mean ‘We two should eat’ referring to persons A and C. The same is true of the ‘dibò-pronouns’ and ‘wáda-pronouns.’

Once again, the ‘goba-pronouns’ have a slightly different behaviour. When at the end of the phrase, acting as locatives, their interpretations are similar to the other locatives. When at the beginning of the phrase, however, they express something different. The inclusive demonstrative ‘si'ídlùtl goba’ refers to two things that are either shared between the speaker and listener(s) or that are more general. The exclusive demonstrative ‘si'ídlòts goba,’ on the other hand, refers specifically to nouns located at or near the speaker’s position or that are held or owned by the speaker. For example, you are holding a dog while your friend is holding another dog. You might say ‘I love these dogs,’ referring specifically to the dog you are holding and the dog your friend is holding. In this case, you would use ‘si'ídlùtl goba.’ However, if you have both dogs with you and are referring to them together, you would use ‘si'ídlòts goba.’ These are quite subtle differences, and a speaker would likely be understood regardless of which of these they use, however, native speakers would still notice the difference. The inclusive demonstrative is also used for generalities, such as in the sentence ‘we all share these two traits.’ In this case, the traits have no specific location and are instead being discussed generally, hence the inclusive demonstrative is used.

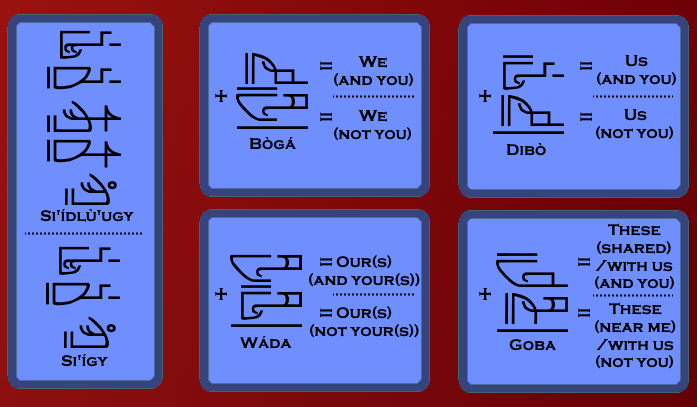

|

The last group of first person pronouns are the plural first person pronouns (figure 3). These are used to refer to more than two of a noun, and follow the same rules as the duals (ie. the inclusive plural includes the person being addressed, while the exclusive plural excludes the person being addressed). Additionally, the behaviour of the plural ‘goba-pronouns’ is identical to their dual counterparts (ie. inclusive refers to shared objects or generalities while exclusive refers to objects near the speaker).

|

Second Person Pronouns are pronouns that refer to the person being addressed and any others (you, your). The singular second person pronouns are shown in figure 4, and follow many of the same rules as their first person counterparts. Notice that English uses the word ‘you’ for both the nominative (eg. You saw him) and accusative (eg. He saw you), while Spiròt distinguishes these two based on the corresponding case marker.

Notice also that the ‘goba-pronoun,’ when acting as a demonstrative, carries additional information. In particular, it refers to an object at the location of the person being addressed. This is known as a Medial Demonstrative, as opposed to Proximal Demonstratives (referring to nouns near the speaker) and Distal Demonstratives (referring to nouns far from both the speaker and the person being addressed). English doesn’t have a specific medial demonstrative, and instead uses the same word (that) for both medials and distals. Other languages, however, such as Japanese, Portuguese and many others, do distinguish between all three.

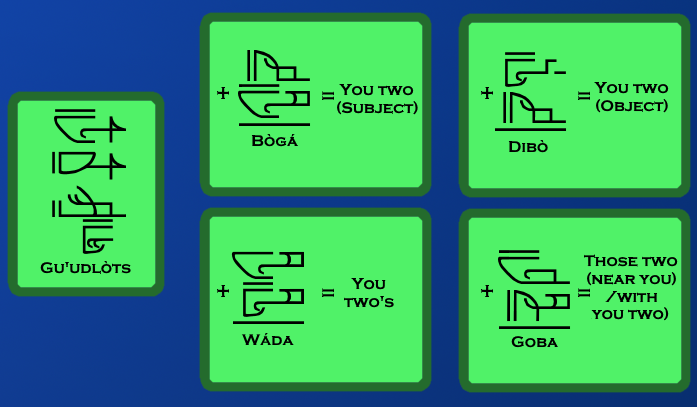

|

The dual second person pronouns (figure 5) are simpler than their first person counterparts, as there is no distinction between inclusive and exclusive. Notice that some of these have somewhat unusual translations, since English doesn’t have separate dual pronouns. Therefore, a phrase like ‘Gu'udlòts wáda yabùtl bògá hlatl’ translates to ‘You two’s animal,’ as in, ‘The animal that is owned by the two of you.’ Note as well that the dual demonstrative pronoun refers specifically to two objects located at the person being addressed. In other words, it is a medial demonstrative, just like the previous demonstrative pronoun.

|

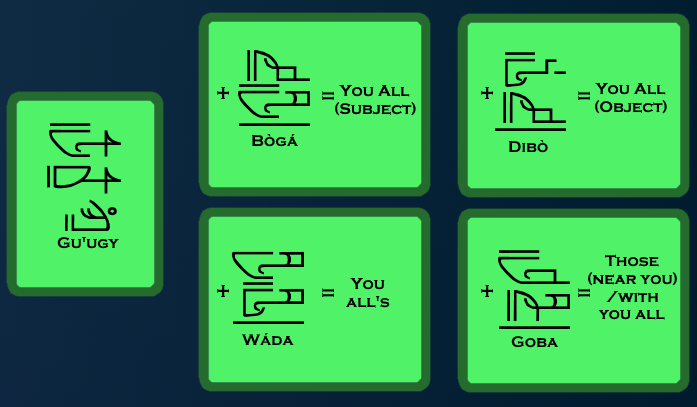

|

Lastly, we have the plural second person pronouns (figure 6). Again, since English uses ‘you’ and ‘your’ in many different contexts, the translations of some of these have been expanded for clarity. For example, when speaking to a group of actors in a play, you might say ‘Your performance was great,’ where ‘your’ refers to the entire group. The Spiròt equivalent to this is ‘Gu'ugy wáda’ which has been translated as ‘you all’s’ for clarity.

|

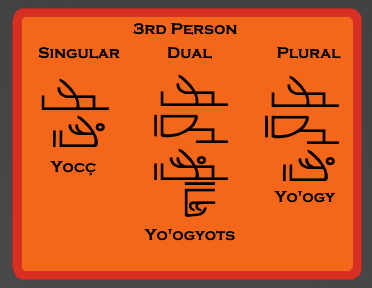

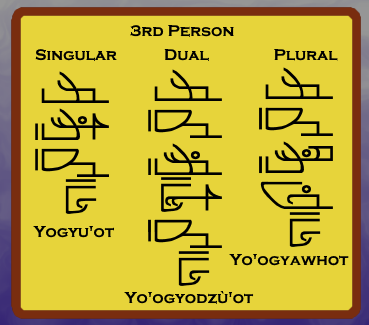

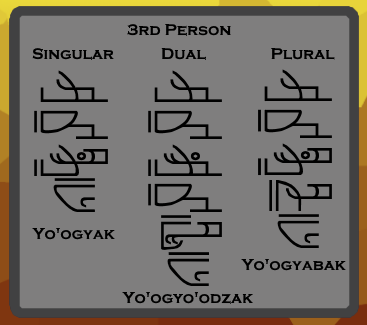

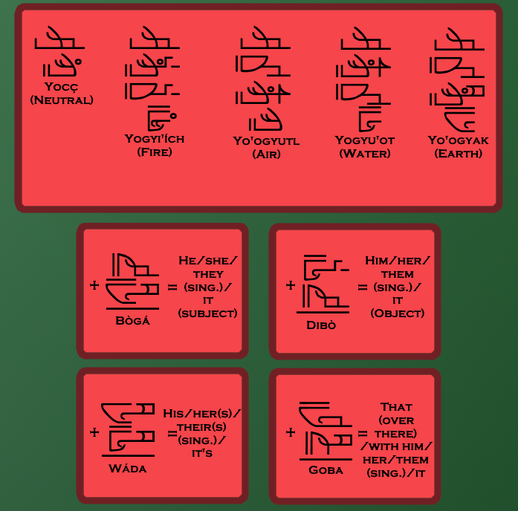

The third person pronouns are somewhat more complicated as, like in English, there are several noun classes to consider. In English, third person pronouns are divided into masculine, feminine and neutral (he, she, and they or him, her and them), as well as an inanimate pronoun (it). While Spiròt doesn’t distinguish between animate and inanimate nouns, it does has five grammatical classes (neutral, fire, air, water and earth) and therefore has five different pronouns for each level of number (singular, dual and plural). The five classed pronouns differ only in who or what they can refer to (eg. fire pronouns are used to refer to fire spiròts or fire class nouns, water pronouns refer to water spiròts or water class nouns, etc.) and otherwise behave identically. Additionally, since groups can often consist of individuals or objects belonging to multiple classes, the neutral pronouns are used in these circumstances, making the other dual and plural pronouns quite uncommon.

The singular third person pronouns are shown in figure 7. Note that the combinations of pronouns and case markers don’t have perfect English translations, but instead depend upon context (eg. ‘Yo'ogyutl bògá’ translates to ‘it’ if referring to an inanimate air class noun, such as the wind, and translates to ‘he’ when referring to air spiròts, as air spiròts are generally regarded as being masculine). Note as well that the demonstratives derived from third person pronouns are distal (ie. they refer to objects far from both the speaker and the person being addressed, which can be translated as ‘that over there’).

The singular third person pronouns are shown in figure 7. Note that the combinations of pronouns and case markers don’t have perfect English translations, but instead depend upon context (eg. ‘Yo'ogyutl bògá’ translates to ‘it’ if referring to an inanimate air class noun, such as the wind, and translates to ‘he’ when referring to air spiròts, as air spiròts are generally regarded as being masculine). Note as well that the demonstratives derived from third person pronouns are distal (ie. they refer to objects far from both the speaker and the person being addressed, which can be translated as ‘that over there’).

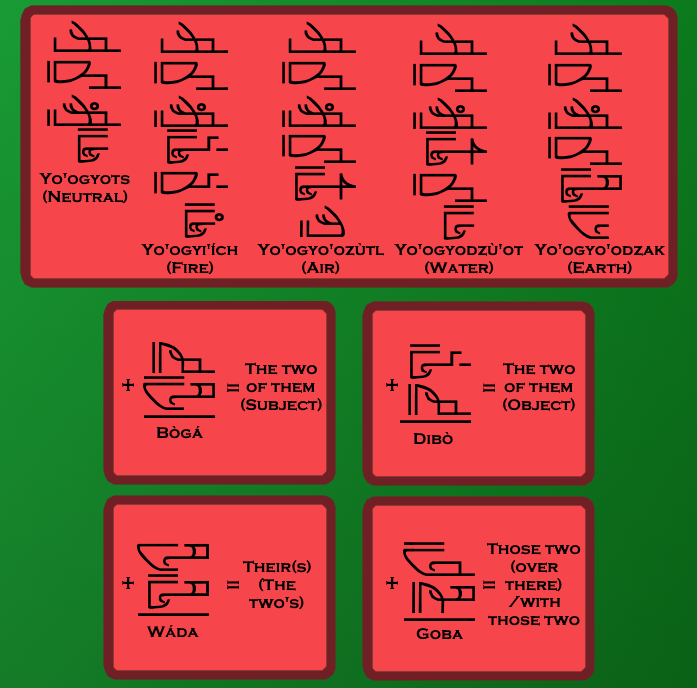

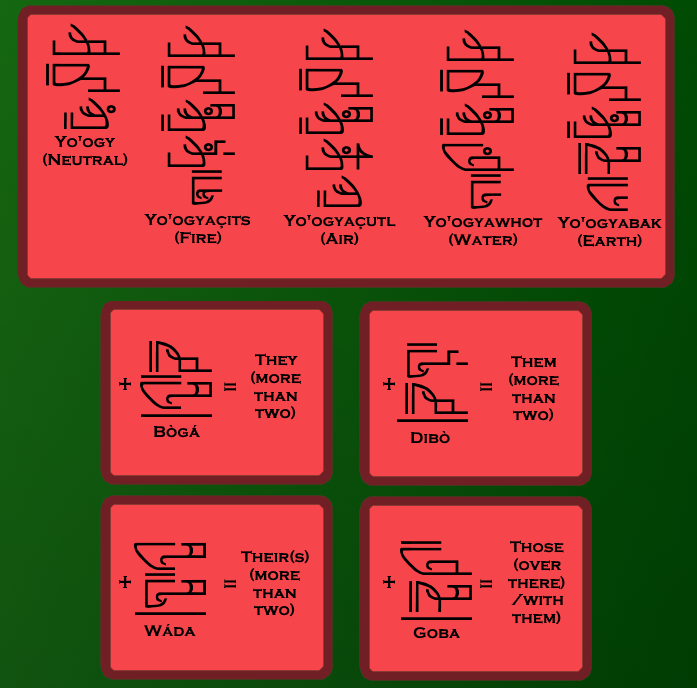

The dual third person pronouns (figure 8) and the plural third person pronouns (figure 9) follow the same rules as previously described, although recall that the neutral forms are most commonly used, with the other forms used mostly to refer to groups of the same type of spiròt or object (eg. two fire spiròts might be referred to using the pronoun ‘yo'ogyi'ích’ while two spiròts of unknown elements would simply be referred to using the neutral ‘yo'ogyots’).

Lastly, it should be mentioned that there are many more pronouns aside from these most common ones, such as reflexive pronouns (myself, yourself, themselves, etc.), indefinite pronouns (somebody, anybody, everybody, etc.) and impersonal pronouns (one, oneself, etc.). These more specific pronouns often only occur in specific environments (eg. the pronoun ‘myself’ wouldn’t be used as a possessive) or behave like their basic counterparts (eg. the singular third person indefinite pronoun ‘one’ is written as ‘fip yocç’ in Spiròt, and behaves similarly to the regular singular third person pronoun, ‘yocç,’ although it cannot be used demonstratively). Therefore, their usage typically follows from the rules for the basic pronouns, and for this reason, they won’t be elaborated upon here.

SECTION III SUMMARY

SECTION III DEFINITIONS

Word Order: The order or arrangement of words in a phrase, clause or sentence. (Source)

Subject: In grammar, a noun, noun phrase, or pronoun that performs the action of a verb in a sentence. (Source)

Verb: In grammar, a word that is usually one of the main parts of a sentence and that expresses an action, occurrence, or a state of being. (Source)

Object: In grammar, a noun, noun phrase, or pronoun that receives the action of the verb or completes the meaning of an adposition. (Source)

Noun Phrase: A phrase formed by a noun and all its modifiers and determiners. (Source)

Modifier: A word, phrase, or clause that gives information about another word in the same sentence. (Source)

Determiner: A word or affix that modifies a noun, expressing the reference and/or quantity of the noun. (eg. the, a/an, this, that, my, your, etc. in English) (Source)

Verb Phrase: A phrase formed by a main verb, any modal and/or auxilliary verbs and any other modifiers. (Source)

Adjective: A word that modifies a noun to indicate quality, quantity, or extent or to distinguish it from something else. (eg. blue, tired, bright, etc.) (Source)

Adposition: An element (eg. preposition, postposition, etc.) that combines with a phrase to indicate how the phrase should be interpreted in the surrounding context. (eg. in, at, on, of, for, etc. in English) (Source)

Postposition: A word that follows a noun and indicates some temporal or spatial relation. Similar to English prepositions, except they come after the noun rather than before. (Source)

Article: A type of determiner that specifies if the noun is general or specific. (eg. the and a/an in English) (Source)

Case Marker: In grammar, a device (word, affix, etc.) associated with a noun phrase that signals its grammatical role. (Source)

Nominative Case: The grammatical case that includes nouns or pronouns that are the subject of a sentence or clause. (Source)

Accusative Case: The grammatical case that includes nouns or pronouns that are the direct object of a verb. (Source)

Genitive Case: The grammatical case that includes nouns or pronouns that indicate possession. (Source)

Locative Case: The grammatical case whose function is to indicate the location of some object or event. (Source)

Postpositional Case Marker: In Spiròt, a word that denotes the case of the preceeding noun or gives some indication of its position.

Number: In grammar, a categorization of nouns, pronouns, etc. that expresses count distinctions. (eg. singular vs. plural in English) (Source)

Noun Class: A grammatical system used by some languages to categorize nouns into classes, often based on the characteristics of the nouns in each class. (Source)

Person: In grammar, a category used to distinguish between those who are speaking, those who are being addressed, and those who are neither speaking nor being addressed. (Source)

Subject Phrase: In Spiròt, the noun phrase containing the subject noun.

Object Phrase: In Spiròt, the noun phrase containing the object noun. In linguistics, the object is often considered part of the verb phrase, which may be called the predicate.

Auxilliary Verb: A verb that is used with another verb to show the verb's tense, mood, to form a question, etc. (Source)

Adverb: A word that typically modifies a verb, but may also modify adjectives, other adverbs, phrases, etc. (Source)

Common Noun: A noun that is the name of a group of similar things, not of a single person, place or thing. (eg. a cat or a town) (Source)

First Person Pronoun: A pronoun that refers to the speaker (or writer) or to a group that includes the speaker (or writer). (eg. I, me, mine, we, us, ours, etc.) (Source)

Second Person Pronoun: A pronoun that refers to the person or people that the speaker is addressing. (eg. you, your, yours, etc.) (Source)

Third Person Pronoun: A pronoun that refers to people or things other than the speaker (or writer) and the person or people being addressed. (eg. he, she, they, it, him, her, them, etc.) (Source)

Singular: In grammar, a type of number that refers to one of a noun. (eg. a dog, the tree, etc.) (Source)

Dual: In grammar, a type of number that refers to exactly two of a noun. (eg. two dogs, the two trees, etc.) (Source)

Plural: In grammar, a type of number that refers to more than one of a noun. (eg. the dogs, the trees, etc.) (Source)

Definite Article: An article that refers to a noun that is a specific thing. (eg. the egg, the house, etc.) (Source)

Indefinite Article: An article that refers to a noun that is not specified. (eg. an egg, a house, etc.) (Source)

Negative Article: An article that refers to none of a noun. (eg. no egg, no house, etc.) (Source)

Personal Article: A subclass of proper articles that refers specifically to the name of an individual. (Source)

Neutral Class: In Spiròt, a noun class that typically contains nouns of space, time and names for broad concepts/groups (eg. moment, place, animal, etc.)

Fire Class: In Spiròt, a noun class that typically contains nouns relating to fire, belief or action (eg. light, faith, jump, etc.)

Air Class: In Spiròt, a noun class that typically contains nouns relating to air, thought or discovery (eg. wind, mind, idea, etc.)

Water Class: In Spiròt, a noun class that typically contains nouns relating to water, emotion or community (eg. river, joy, unity, etc.)

Earth Class: In Spiròt, a noun class that typically contains nouns relating to earth, physicality or physical objects not belonging to another class (eg. rock, fight, eye, etc.)

Declension: The inflection of nouns, pronouns, adjectives or other parts of speech for case, number, gender, class, or some other category. (Source)

Suffix: An affix (sounds and/or letters attached to a word) added to the end of a word. (Source)

Pronoun: Any of a small set of words in a language that are used as substitutes for nouns or noun phrases. (eg. I, me, you, we, our, they, their, etc.) (Source)

Personal Pronoun: A pronoun that expresses a distinction of a person. (eg. I, you, they, etc.) (Source)

Possessive Pronoun: A pronoun that replaces a noun and shows ownership. (eg. Mine, yours, theirs, etc.) (Source)

Possessive Determiner: A word used with a noun that expresses possession or belonging. (eg. My, your, their, etc.) (Source)

Demonstrative: In grammar, a word that points out the one referred to, distinguishing it from others of the same class (eg. This, that, those, etc.) (Source)

Demonstrative Pronoun: A word that replaces a noun and is used to point to specific objects. (eg. This is difficult, that is far away, etc.) (Source)

Demonstrative Determiner: A word that occurs with a noun and is used to point to specific objects. (eg. This puzzle is difficult, that mountain is far away, etc.) (Source)

Inclusive Pronoun: Pronouns that include the person being addressed (eg. You and I, Us (including you), etc.) (Source)

Exclusive Pronoun: Pronouns that exclude the person being addressed (eg. We (excluding you), Us (excluding you), etc.) (Source)

Proximal Demonstrative: A word used to point to an object close to the speaker. (eg. This, these) (Source)

Medial Demonstrative: A word used to point to an object close to the person being addressed. (eg. that (near you), those (near you)) (Source)

Distal Demonstrative: A word used to point to an object far from both the speaker and the person being addressed. (eg. That (over there), those (over there)) (Source)

Subject: In grammar, a noun, noun phrase, or pronoun that performs the action of a verb in a sentence. (Source)

Verb: In grammar, a word that is usually one of the main parts of a sentence and that expresses an action, occurrence, or a state of being. (Source)

Object: In grammar, a noun, noun phrase, or pronoun that receives the action of the verb or completes the meaning of an adposition. (Source)

Noun Phrase: A phrase formed by a noun and all its modifiers and determiners. (Source)

Modifier: A word, phrase, or clause that gives information about another word in the same sentence. (Source)

Determiner: A word or affix that modifies a noun, expressing the reference and/or quantity of the noun. (eg. the, a/an, this, that, my, your, etc. in English) (Source)

Verb Phrase: A phrase formed by a main verb, any modal and/or auxilliary verbs and any other modifiers. (Source)

Adjective: A word that modifies a noun to indicate quality, quantity, or extent or to distinguish it from something else. (eg. blue, tired, bright, etc.) (Source)

Adposition: An element (eg. preposition, postposition, etc.) that combines with a phrase to indicate how the phrase should be interpreted in the surrounding context. (eg. in, at, on, of, for, etc. in English) (Source)

Postposition: A word that follows a noun and indicates some temporal or spatial relation. Similar to English prepositions, except they come after the noun rather than before. (Source)

Article: A type of determiner that specifies if the noun is general or specific. (eg. the and a/an in English) (Source)

Case Marker: In grammar, a device (word, affix, etc.) associated with a noun phrase that signals its grammatical role. (Source)

Nominative Case: The grammatical case that includes nouns or pronouns that are the subject of a sentence or clause. (Source)

Accusative Case: The grammatical case that includes nouns or pronouns that are the direct object of a verb. (Source)

Genitive Case: The grammatical case that includes nouns or pronouns that indicate possession. (Source)

Locative Case: The grammatical case whose function is to indicate the location of some object or event. (Source)

Postpositional Case Marker: In Spiròt, a word that denotes the case of the preceeding noun or gives some indication of its position.

Number: In grammar, a categorization of nouns, pronouns, etc. that expresses count distinctions. (eg. singular vs. plural in English) (Source)

Noun Class: A grammatical system used by some languages to categorize nouns into classes, often based on the characteristics of the nouns in each class. (Source)

Person: In grammar, a category used to distinguish between those who are speaking, those who are being addressed, and those who are neither speaking nor being addressed. (Source)

Subject Phrase: In Spiròt, the noun phrase containing the subject noun.

Object Phrase: In Spiròt, the noun phrase containing the object noun. In linguistics, the object is often considered part of the verb phrase, which may be called the predicate.

Auxilliary Verb: A verb that is used with another verb to show the verb's tense, mood, to form a question, etc. (Source)

Adverb: A word that typically modifies a verb, but may also modify adjectives, other adverbs, phrases, etc. (Source)

Common Noun: A noun that is the name of a group of similar things, not of a single person, place or thing. (eg. a cat or a town) (Source)

First Person Pronoun: A pronoun that refers to the speaker (or writer) or to a group that includes the speaker (or writer). (eg. I, me, mine, we, us, ours, etc.) (Source)

Second Person Pronoun: A pronoun that refers to the person or people that the speaker is addressing. (eg. you, your, yours, etc.) (Source)

Third Person Pronoun: A pronoun that refers to people or things other than the speaker (or writer) and the person or people being addressed. (eg. he, she, they, it, him, her, them, etc.) (Source)

Singular: In grammar, a type of number that refers to one of a noun. (eg. a dog, the tree, etc.) (Source)

Dual: In grammar, a type of number that refers to exactly two of a noun. (eg. two dogs, the two trees, etc.) (Source)

Plural: In grammar, a type of number that refers to more than one of a noun. (eg. the dogs, the trees, etc.) (Source)

Definite Article: An article that refers to a noun that is a specific thing. (eg. the egg, the house, etc.) (Source)

Indefinite Article: An article that refers to a noun that is not specified. (eg. an egg, a house, etc.) (Source)

Negative Article: An article that refers to none of a noun. (eg. no egg, no house, etc.) (Source)

Personal Article: A subclass of proper articles that refers specifically to the name of an individual. (Source)

Neutral Class: In Spiròt, a noun class that typically contains nouns of space, time and names for broad concepts/groups (eg. moment, place, animal, etc.)

Fire Class: In Spiròt, a noun class that typically contains nouns relating to fire, belief or action (eg. light, faith, jump, etc.)

Air Class: In Spiròt, a noun class that typically contains nouns relating to air, thought or discovery (eg. wind, mind, idea, etc.)

Water Class: In Spiròt, a noun class that typically contains nouns relating to water, emotion or community (eg. river, joy, unity, etc.)

Earth Class: In Spiròt, a noun class that typically contains nouns relating to earth, physicality or physical objects not belonging to another class (eg. rock, fight, eye, etc.)

Declension: The inflection of nouns, pronouns, adjectives or other parts of speech for case, number, gender, class, or some other category. (Source)

Suffix: An affix (sounds and/or letters attached to a word) added to the end of a word. (Source)

Pronoun: Any of a small set of words in a language that are used as substitutes for nouns or noun phrases. (eg. I, me, you, we, our, they, their, etc.) (Source)

Personal Pronoun: A pronoun that expresses a distinction of a person. (eg. I, you, they, etc.) (Source)

Possessive Pronoun: A pronoun that replaces a noun and shows ownership. (eg. Mine, yours, theirs, etc.) (Source)

Possessive Determiner: A word used with a noun that expresses possession or belonging. (eg. My, your, their, etc.) (Source)